“The Deification of Numbness” – The Misadventure of Mr. Ginger Baker And The Destruction Of Rock’n’Roll

MIKE EDISON, author of forthcoming book Sympathy for the Drummer: Why Charlie Watts Matters, considers the unexpected impact of GINGER BAKER on the death of rock ‘n’ roll

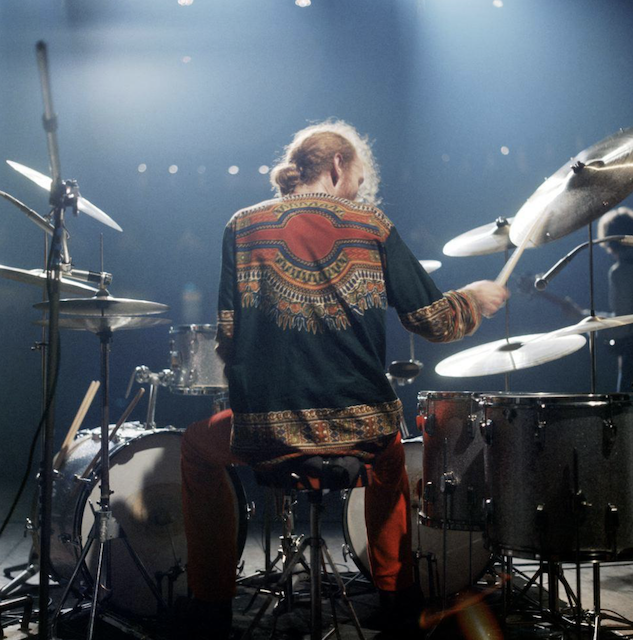

It’s a shame that Ginger Baker, the cantankerous, boisterously assaultive drummer (both when it came to hitting the drums, and other people) who died this week at the age of 80, couldn’t make a real go of it playing jazz. As it is, he made his bones playing in an over-amplified blues band, that’s where the money was. That, too — although there was no way of knowing it at the time — was where the future of rock aristocracy took hold.

Maybe Ginger couldn’t have gone toe-to-toe with Elvin Jones or Max Roach, but he could certainly have played in their league, given the opportunity. He duelled wonderfully with Art Blakey, he was that good a jazzer. He had the hands, and, once upon a time, the heart.

The received wisdom regarding Ginger baker, of course, will always be that he “redefined rock drumming”, and like most urban legends, this is one that has been fuelled by ignorance and confusion.

He was flamboyant, and accomplished, but there was nothing he did within the realm of rock ’n’ roll that stood out as a teaching moment. Even his most fawning obituaries, while gushing about being the first rock drummer to make the extended solo part of the shtick – yes, you can blame him for that – can’t seem to find one stylistic tic to mention that changed drumming for the better, like John Bonham’s triplets and mind boggling-bass drum control; James Brown’s drummers’ (namely Clyde Stubblefield and Jabo Starks) maddening aversion to the backbeat; Keith Moon’s unparalleled charisma and abandon; Mitch Mitchell’s jazzy flow within the uncharted acid-rock peregrinations of Jimi Hendrix; or Al Jackson’s erotic pulse with Al Green. In Cream, there was nothing that was revolutionary or evolutionary, unless you consider his contribution to vaunting loud, breathless jams to the forefront of the rock concert experience, and placing awesome-looking but ultimately unnecessary double bass drums at the center of maximalist power bands. And of course, the mandatory drum solo, also known in less polite circles as “pee time”.

Undoubtedly, Ginger could play circles around most other so-called “rock” drummers, but it was only after years after being forced to listen to the middling psychedelic pop singles Cream perpetrated, whose saving graces were often Eric Clapton’s sharp and uncharacteristically succinct guitar solos (thank God for AM radio), and more often, their ponderous jams — which titillated teenage boys just learning to play their instruments as if they were some sort of musical pornography – when I heard him playing genuine jazz or Afrobeat, that I got a real sense of how inordinately talented a drummer he truly was.

But at the peak of his fame, he was one of those guys culpable for pushing all of the nuance out of playing the blues. Cream’s version of ‘Spoonful’, one of Howlin’ Wolf’s most meditative and darkest numbers, a one-chord, modal tone poem dedicated to murder and drugs and love and money, was especially painful, often catapulting into sprawling, meaningless adventures in cacophony that excised any emotional content from the song, their collective instrumental chops notwithstanding.

Lester Bangs called it “the deification of numbness”. It was rock without the roll, and the damage Ginger did, along with his bandmates Eric Clapton and Jack Bruce, justifying a fresh genre of ego-tripping, self-fellating jamming, can still be felt. It stomped, it didn’t swing, a serious crime for a cat who was in reality a top flight jazz drummer.

Baker had stamina and flair, and a without a doubt a certain impenetrable, undeniable style, but his overpowering onslaught of muscle and technique that became the coin of the realm in Cream always seemed to put the drummer in front of the song, and not in the supporting role that the gig largely calls for. As I have said elsewhere, this is the sort of thing that takes the virtue out of virtuosity.

Of course obituaries for aging rock stars are often written years in advance, and sit decaying, just waiting for the first sentence to be written – it isn’t an art form necessarily known for newfound introspection, and classic rock icons, especially, have lately been awarded the nobility of the saints. Now that it is becoming clear that as a race, their time with us is becoming palpably limited, sentiment is replacing sense, nostalgia sitting in for hard-earned knowledge. As it was stated in a mediocre Schwarzenegger movie that will likely someday be heralded as a one of the great sci-fi flicks of our time, “your memories have been faked”.

Ironically, Ginger Baker crossed paths professionally with Charlie Watts, whose minimalism lies in stark contrast to Baker’s wide-open assault, when Charlie left Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated in 1963 to join the Stones, and Ginger took the chair.

Charlie, too, was a jazz drummer who lowered his career expectations to play tawdry blues and rock music. In fact they were good friends. Charlie couldn’t play on the technical level of Ginger, but as a rock’n’roll drummer with a determined sense of swing, Charlie was able to roll his band into the future. With Cream, whom he joined a few years later, Ginger Baker seemed to spend as much of his time just trying to keep up with his band, both in volume and number of notes played — it often seemed as if they were competing with each other, rather than playing together.

Despite a career that lasted a scant two years – they self-immolated in1 968 after four records of varying quality – Cream will always be Ginger Baker’s legacy band. His iterations of the Air Force aren’t in heavy rotation for good reason. Blind Faith had their day in the sun, and a few genuine high moments, but his gig in Public Image Ltd. was the rock music equivalent of stunt casting.

Sadly, far too few rock fans were hip to the recordings he made in Africa, especially the hot blast with Fela Kuti. Like Lenny Bruce, that part of his career will always be something more people have heard of than have actually heard, but that’s where he proved that he held something precious few others could control, mesmerizing, driving, polyrhythmic Nigerian beats, tempered with extended jazz chops.

Moon couldn’t touch that, nor Bonham, nor Watts. Well, maybe Bonham, if he put his mid to it, but as crazy a drummer as he was, he wasn’t going to climb into a Land Rover and drive across the Sahara to find his muse. Which is at least one reason to admire Ginger Baker. It is blessing and curse to be born with such talent. It made him a drumming superstar, and it was also likely his ultimate downfall, not quite fitting in anywhere, not for any extended length of time. His talent was vast. Perhaps the world was just too small.

Info on the book here