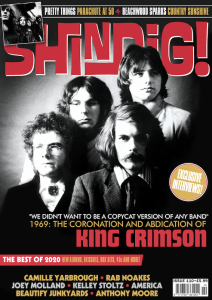

King Crimson: “The spirit of KC ’69 was an open collaboration of ideas, energy, freedom of expression, spontaneity and taking risks by going into the unknown”

As a taster for our December cover feature on the origins of KING CRIMSON, in an exclusive interview, original drummer and co-founder MICHAEL GILES speaks to MARTIN RUDDOCK about those early days

Shindig!: You formed Giles, Giles & Fripp with your brother Peter and Robert Fripp after Fripp answered an ad for a singing organist. He was neither of these, but you formed a trio anyway. What were your first impressions of Fripp?

Michael Giles: I was firstly impressionised by Robert’s sheer audacity in applying for a position for which he had absolutely no qualifications, or even latent talent. Secondly, Peter and I were very impressed with Robert’s left-handed dexterity for fingering strings and frets to navigate alternative courses through little known Norwegian sequences. Thirdly more, and perhaps the essential reason for asking him to join us, was the fact that he had a van which of course would be necessary if we were booked to play toilet tours down and up this great country of ours.

So imagine our dis-impression when Robert abandoned his van in Wimborne just before our move to London, whereupon we had to squeeze our suitcases, instruments and equipment into Peter’s old preselector gearbox Daimler saloon and my old pea-green side-valve two door Ford Anglia, registration number MRU 7 – a good old Bournemouth number plate which I wish I’d kept.

SD!: What are your memories of recording GGF’s album for Deram, The Cheerful Insanity Of Giles, Giles & Fripp?

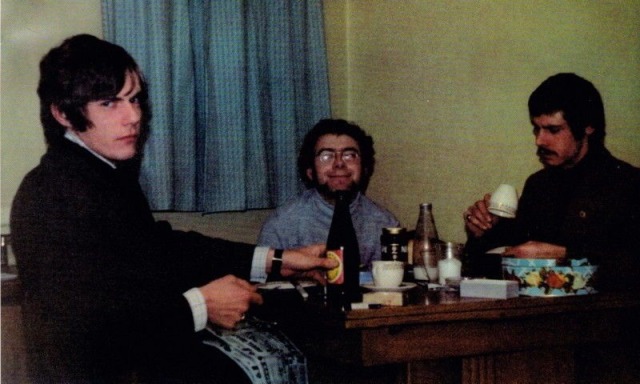

MG: We recorded The Cheerful Insanity Of at Decca Studios in West Hampstead – fairly near Brondesbury Road where we lived and recorded the demos. The Decca studios were in a large old building, maybe an old church, inhabited by serious middle-aged maintenance technicians wearing spectacles and long white laboratory coats. For some unknown reason we were assigned to a producer called Wayne Bickerton who seemed to be somewhat apathetic towards our cheerfully insane way of making music. However, we were blessed by working with the brilliant young sound engineer Bill Price who enjoyed smoking copious amounts of menthol cigarettes while diligently carrying on recording after Wayne went home.

We had lots of fun during those sessions but we had to stop laughing when I, with a cold in my ears, nose and throat, was recording the vocals for ‘The Sun Is Shining’ – live with the girl vocal backing group The Breakaways plus a 12 piece mini orchestra. I think we did it in two or three takes, but if I, The Breakaways or the orchestra had started laughing while recording this silly, soppy, satirical song, it would have taken many more takes to make it a seriously meaningful M.O.R. song about lost love – let alone running into Musicians Union strict rules about big overtime fees for session musicians and singers. I don’t know if The Breakaways were sniggering in between their vocal lines but if they were I didn’t hear it and I couldn’t look at them in case we all collapsed into fits of giggling. When the orchestra packed up and left, I wanted to see how the song arrangements looked on sheets of paper abandoned on their music stands, and I found some boldly written words under the song title – THE SUN IS SHINING – “and it’s shining up my arse!”

Moreover, the sun did not shine on my ambition for someone at Decca to get Ken Dodd to make it a Top 10 Hit Single.

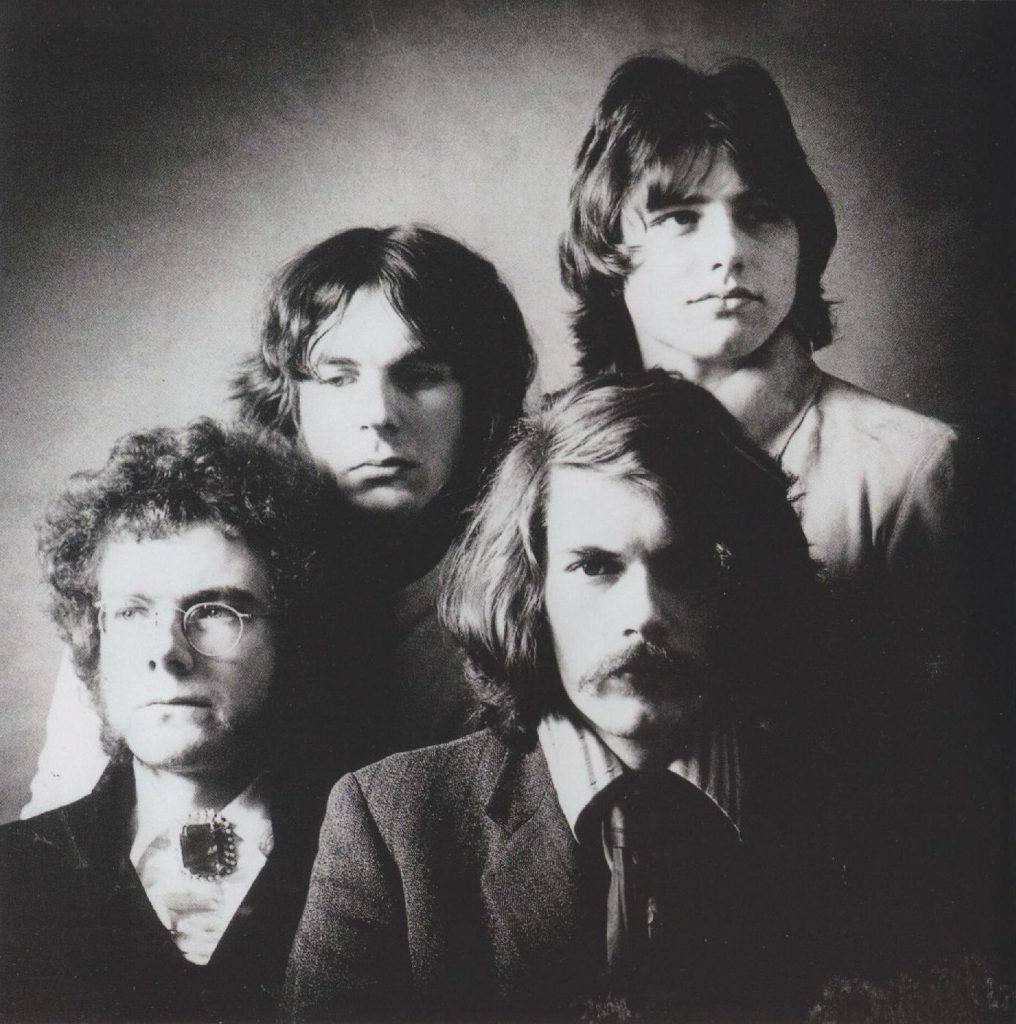

SD!: GG&F were together a year or so. The band expanded in 1968 when Ian McDonald joined, and briefly Judy Dyble as well, before King Crimson mk1 came together in late ’68. I read that Peter left the band when Fripp suggested that Greg Lake joined as Peter’s replacement – or as his. What really happened there, did Robert just not want to play with Peter anymore? Was his departure awkward for you?

MG: I was surprised and disappointed by Peter leaving after enjoying 10 years of a symbiotic bass and drums partnership. But his decision was probably based on all our good work resulting in a spectacularly successful lack of success. It was only after Peter left that Robert suggested Greg Lake who had a unique powerful voice and was willing to be taught by Robert how to play bass guitar, which came to sound more like a guitar player playing bass rather than a bass player playing bass. I would have been happy with Greg on lead vocals and second guitar and Peter’s brilliant bass playing, but this was never discussed by any of us because Peter’s swift departure was well before Greg’s arrival. This change of personnel was conducted with the utmost amicability and “in the best possible taste”. However, Greg’s vocals, Peter’s bass and my drums did eventually come together on KC’s In the Wake of Poseidon.

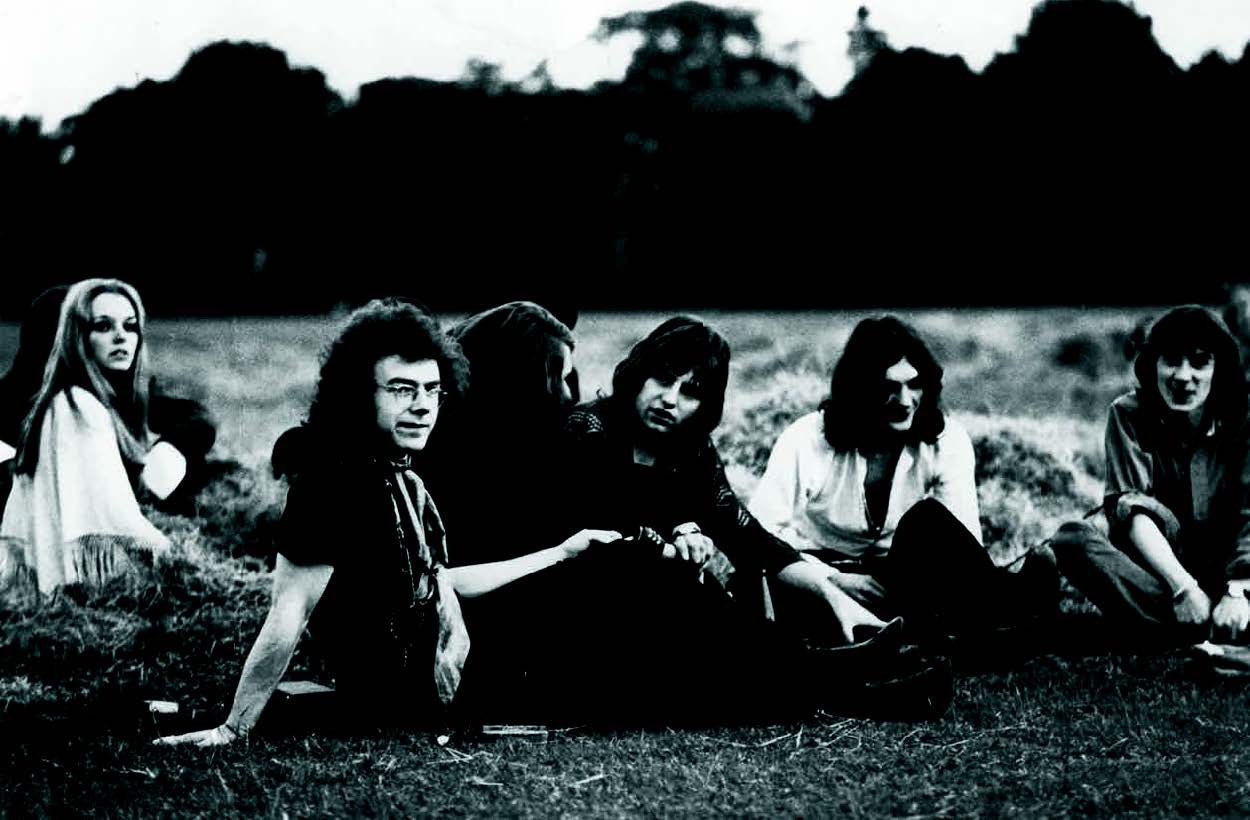

SD!: King Crimson were a huge success out of nowhere. Three months after your first gig at The Speakeasy you were playing for a huge audience opening for the Stones in Hyde Park. What was that gig like?

MG: The Hyde Park concert was a very important event in the band’s rapid rise to international recognition. We played a shortened set fairly well on a very large stage. Because we were so spread out across the stage with inadequate stage monitoring it was difficult to hear each other, so we had to rely on our well rehearsed routines. Fuelled with adrenaline, the tempos may have been a little too fast, perhaps also due to CBS – acronymical muso-speak for Clenched Buttock Syndrome.

During the set we played some somewhat jokey British improvisations which must have surprised many people amongst the guestimated hundreds of thousands who were there to see the black blues-based Rolling Stones rocking and rolling. Although Mick Jagger wore a girl’s short white cotton summer frock and paid tribute to Brian Jones, their set was probably not one of their best. Nevertheless, Mick cavorted all over the stage, Keith kept his guitar slung low over his knees, Bill played the bass guitar vertically under his chin and Charlie wore his customary dead-pan face.

So quite a Rolling Stoned show after the recent death of Brian Jones and their two years away from public performance. Anyway, the audience were impressed with KC, enough to pack out The Marquee Club every time we played there.

SD!: KC first went into the studio with Moody Blues producer Tony Clarke, but it didn’t work out. Why was that?

MG: For some unknown and perhaps spurious reasons Tony Clarke tried to transform and tame the wild energy of King Crimson into another smoothly controlled echo-washed version of The Moody Blues by using the same old production formula (especially acres of multi-tracked strumming guitars) which gave rise to the Satin Knights’ success.

However, we did not regard ourselves and our music as moody or bluesy, nor did we wear white satin knightgowns. We didn’t want to be a copycat version of any band. So without wasting time looking for a producer who would honour our music, we decided to take the risk of producing it ourselves. If we made a mess of it, we would be to blame – not someone else. Our enthusiasm for self-expression combined with confidence soonly produced an album which genuinely represented our music.

SD!: Crimson really brought out the best in all of you, playing-wise. Your drumming on In The Court Of The Crimson King is some of the most inventive to be put down on record, full stop. Was there maybe a feeling of competition within the band, driving each other to new heights as players?

MG: As far as I’m aware there was no competition to be the best musician in the band – it was enough for me to be competing with myself. We all played to the best of our ability, encouraged and stimulated to go further by what the others were playing, and my drumming on ‘In The Court Of’ is a natural instinctive human response to the sounds created around me by Robert, Ian and Greg plus Pete’s words. The spirit of KC ’69 was an open collaboration of ideas, energy, freedom of expression, spontaneity and taking risks by going into the unknown.

SD!: It was obviously an intensely creative period for all of you, but do any memories of recording In The Court Of The Crimson King particularly stick out for you?

MG: Although the sessions were intensely creative we also had lots of fun, especially in the making of ‘Moonchild’. It was one of Ian and Pete’s ideas for a wistful song, but without an ending, and this invited an instrumental extension whether or not it would return to the melody.

So when the song section ended, our little trio of Robert, Ian and myself carried on spontaneously without a care about what might happen, where it would go and how or when it would end. I was pussy-footing mainly on tom-toms muffled with fluffy yellow dusting cloths. Ian had parked his Mellotron in an underground keyboard park and came back to find himself standing behind an abandoned vibraphone which, as a multi-instrumentalist, he was compelled to play. Robert was perched on a stool in his preferred position as guitar master, with no inclination towards fingering the holes in a water-filled ocarina.

Ian was floating on the vibes, Robert was listening for a good moment to creep in, and I was enjoying their sounds waiting for an opportunity to respond. Our gently-as-you-go trio became more responsive to each other’s spontaneous playing as we went on. We were playing and listening simultaneously in a beautiful bubble of musical awareness, which often happens when surrendering egotistic desires to the unknown energy of nature and the universe.

Of course I can’t speak for Ian and Robert whose views might differ from mine. But I do think we would all agree that it was an enjoyable adventure into empty space, open time and silence. We were not improvising, as in trying to improve something. We were going with the flow of sounds without forcing anything. The music was playing us.

For me, there are many amazing incidents of coincidence that occurred while we were strolling through ‘Moonchild’s garden. One moment in particular occurs later on when Ian plays a fast trill on vibes at exactly the same time as I play a fast trill on cymbals. Ian and I could not see each other from opposite ends of Wessex’s large orchestral studio, so was this brief moment just an incredible coincidence, synchronised trilling or invisible musical telepathy? We’ll never know but I’m happy that it happened.

I played the track recently and the 12-minute original version is definitely not too long – I wanted it to continue. So those who exist in human hurry-time, who want factory-made armour-plated mechanical music-by-numbers and who refuse to go with the natural ebb and flow of free spontaneous music (but can just about put up with the shorter edited version) should be put on trial for treason against the Crimson Kingdom.

SD!: During the US tour at the end of 1969, both yourself and Ian decided that you were leaving which led to the mk 1 band’s split when Greg decided to quit as well. The live tapes from that tour show a band at the peak of its powers. You were also playing new material. Was it musical or personal differences, or were you not keen being on the road?

MG: We each had various, different and some similar musical and personal reasons for leaving.

I decided that my musical freedom was only one important part of the freedom to be a whole human being – not just a narrowly intensively focused musician dedicating his life to being in a rock band, separated from simple living for many months every year. It was a good decision leading to being creative in other areas of my life. Also, the shenanigans of being in a rock band, especially a fastly famous one, gave rise to various unexpected pressures and stresses that my genetic code was not designed to cope with. I didn’t want to live in or out of a suitcase, even with H1 visas, long black limos, jumbo jets and 7 star hotels infested with drug pushers and avid female plaster casterers.

I remember thinking that all those hours per year spent travelling could be used for creative living, including making music, having fun and enjoying the simple uncontaminated aspects of life on earth. The lack of contact with nature and separation from ordinary life was not efficacious for my well-being. Also I did not want to be in the big music business which attracts a strong contingent of mercenary barrow boys, spivs, mafia types and various other money-grabbing sycophants and parasites. Their ruthless exploitation of tunnel-vision musicians’ naivety is little better than the pernicious pursuits of footpads, cut-throats and tearaways on the streets of Victorian London.

Musicians need to be aware of the high price of so-called success. As we know, most bands are formed with a shared purpose and then break up when they become rich, famous and successful, which was beginning to happen to KC. I found touring to be tedious, tiresome, turgid and tawdry. And if you become famous you become public property, which can impede your progress when buying underpants at Marks & Spencers – as it were, if you will, so to speak.

Also, I didn’t like being a passive passenger on tour and hanging around for some 12 hours a day. I heard Brian Eno talking about this in a recent TV interview, and he echoed my own thoughts along the rhetorical lines of – “Why get involved in fame-laden shenanigans just for the sake of two hours on stage, like a performing monkey.”

No wonder you get such big performances from rock bands, because they are effectively shut up in cages, shut up in cars, aircraft, hotel rooms and other claustrophobic spaces with little chance of healthy physical exercise. This is similar to what performing lions were subjected to in the circus. They were shut up in cages all day and let loose for a performance in the evening. That’s the way I saw it, and of course there were money-hungry music-biz men cracking the whip backstage. It seemed pretty sick to me, and sadly dependent on musicians’’naive compliance and personal ambitions.

Prior to KC I’d been on the road for some six years cramped in a van. When we four members of KC were starting on the road squashed into a small Volkswagen Beetle travelling “up t’north”’on the M1 motorway, all I wanted to do was to stop the car, jump out, run up the embankment, leap over a fence and roll over on the wet grass in a farmer’s field. I enjoy being off-road.

In conclusion, here’s a concise version of King Crimson 1969 written in Ye Olde English vernacular as a coda –

Tis iy ay umbul drummurr, loweste ov tha lowe onn ay stule wot av spaykund uppon ay kort ov pennilus grovvalin minstruls hoo purrcharnse dun wot thae dunneth inn tymz ov yoor tu errn ann onneste grote.

Yay twas thae wot verryly fidduld ann didduld inn uh muddee-spune dunjun, onn thu rowde too hoo-noze-wair.

Butt wiv ay feuh flix ov thair defft meuwzikal rists (anned ankuls) thae wurr trusst uppapon ay rair-hayzin rywde too plae too fowzunz ov forrun peepuls wot ad boort thair wreckords.

Ven loe un beeold, ann wiv anuvva phewe flix ov thair rists thae wrent thair sepperut waze.

Hougheavurr, thayd mayd thair marck onn twenniuff sentree meuwzik.

© Michael Giles 2020

Shindig! issue #110 is out on 4th December. Pre-order here.