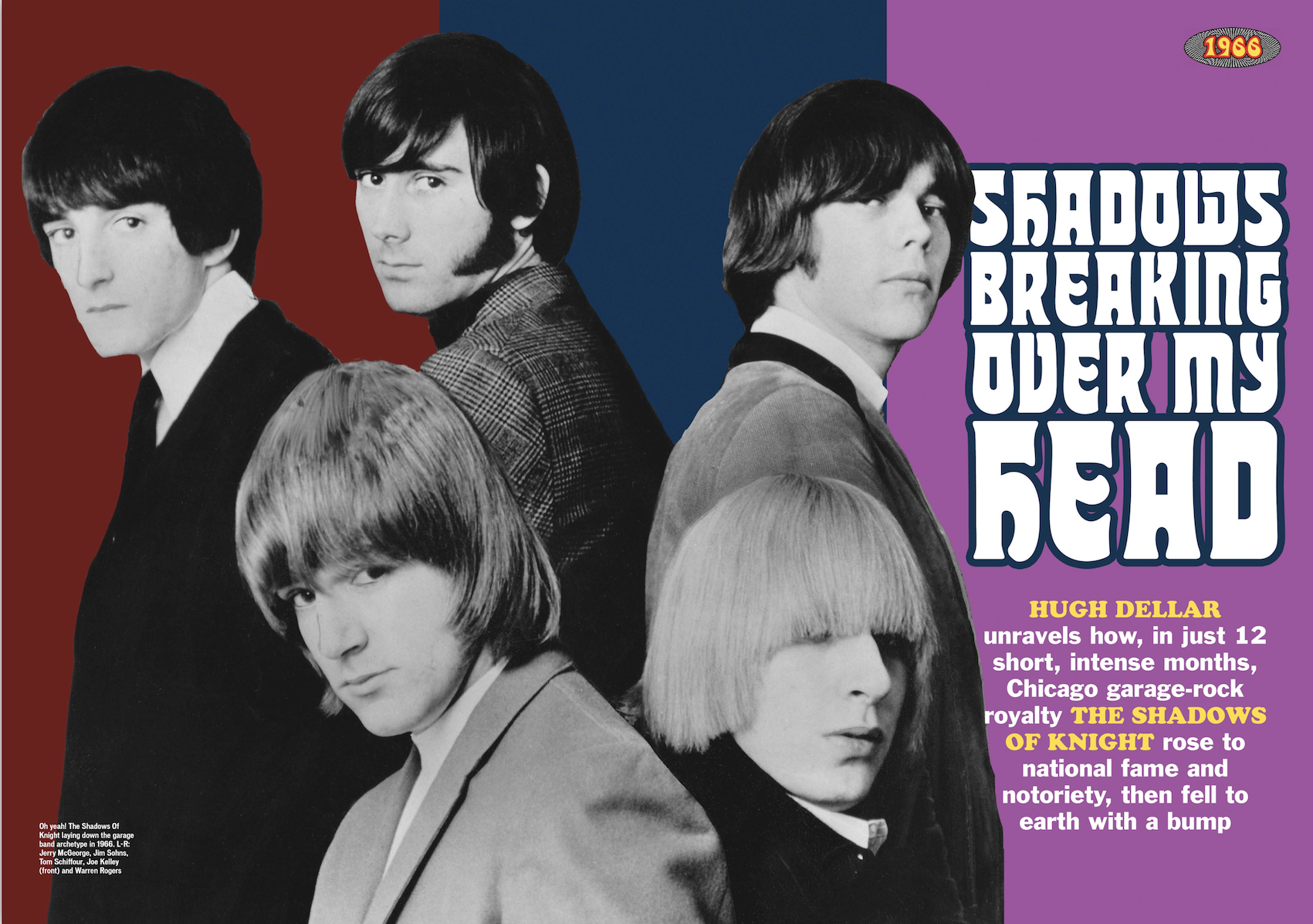

The Shadows Of Knight… RIP Jim Sohns

To pay respect to the enigmatic SHADOWS OF KNIGHT singer Jim Sohns, who has just passed away, here’s a feature that originally appeared in issue #53

Had Van Morrison’s vocal delivery and mode of expression not been quite so leering and lascivious, 1966 could very easily have been a far less remarkable year for Chicago’s Shadows Of Knight. Following its American release, the top side of Them’s debut 45, the lean, mean slash and burn of ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’, somehow failed to set the charts alight and the single could easily have sunk with merely a ripple had it not been for the fact that some savvy DJs bothered to check out the flipside as well. There they found a three-chord original, ‘Gloria’, that perfectly captured the strut and thrust of teenage lust. With its rabble-rousing, lemme-spell-it-out-for-you G-L-O-R-I-A chorus and its sweat-and-other-bodily-fluids-stained breakdown, during which Belfast’s finest son informs listeners that his young lady of choice “Come to my room and make me feel alright”, it soon became a smash in select pockets of the nation, most notably Florida and Texas, forcing its way into the set lists of countless garage bands as it did so.

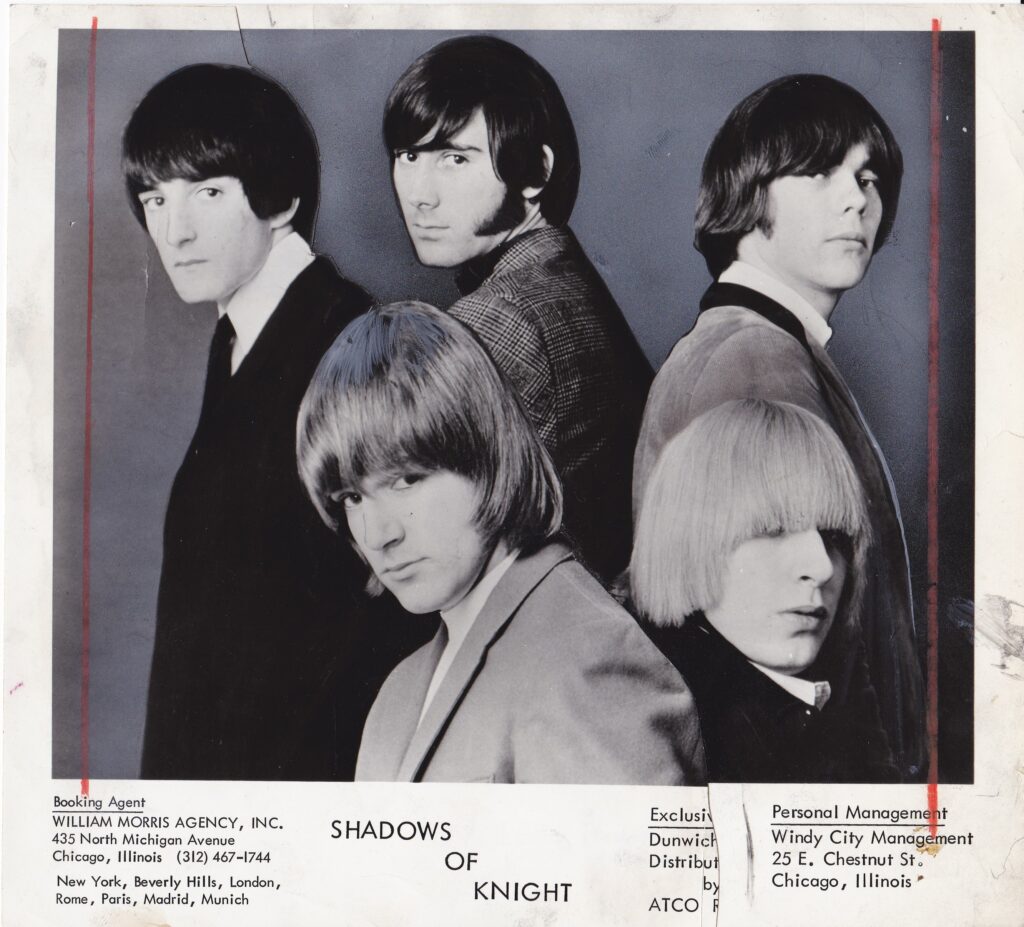

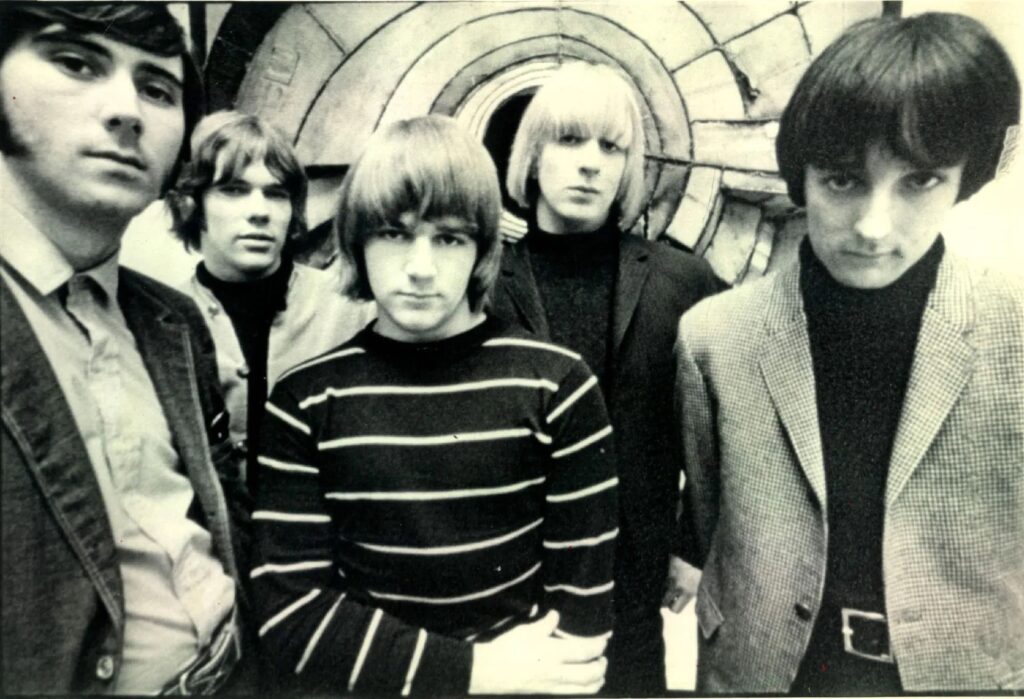

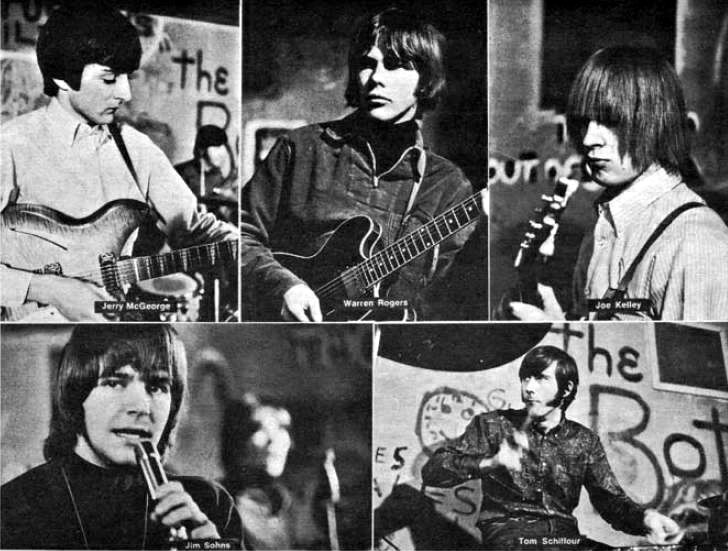

For much of middle America, however, the overt sensuality of the track in general, and of the lines above in particular, proved problematic and radio bans started affecting sales potential, which brings us neatly back to the heroes of this piece. Originally formed in the north-western suburbs of Chicago in early ’65, just as Them were starting to bust out all across the steamy southern states, and initially known simply as The Shadows, this explosive five-piece soon wangled a gig as house band at the Arlington Heights club the Cellar, where they proceeded to build up a fanatically loyal local following with hour-long sets every Friday and Saturday night. The venue was owned by a local booking agent called Paul Sampson, who had countless connections across the city. One of his more influential friends was an older ex-saxophonist, Bill Traut, who’d worked in A&R for Contemporary Records back in the ’50s and had then moved into music programming for the Seeburg Corporation, producers of deluxe jukeboxes and fortuitously housed in the same building as both WLS, the area’s most prominent AM radio station, and the Universal Recording Studios.

By the middle of the decade, Traut had teamed up with Eddie Higgins, an engineer at Universal, and producer George Badonsky and the trio had started putting out their own releases, initially on Amboy (after Badonsky’s hometown) and then on Dunwich, a name they borrowed from a fictional town in a short story by horror writer HP Lovercraft. Sensing that the Windy City’s existing labels already had most of the electric blues, soul and R&B side of things pretty well covered, Dunwich sensed that long-haired, white-boy groups may well prove to be their route to plugging that magical gap in the market. So it was that after persistent badgering from Paul Sampson, the Shadows auditioned and were duly snapped up. Plans for a high-impact debut release were duly set in motion.

Traut had become friends with a WLS DJ, Clark Weber, who’d already witnessed the new signings in action on several occasions, at shows he’d been booked to spin discs at. One day, Weber let slip that while Them’s original of ‘Gloria’ may have been pulled after a solitary spin, he still felt that a cleaned-up version would stand a good chance of garnering considerable airplay, especially if it was by a local act, given the station’s drive towards showcasing the best of the city’s emerging talents. Both men were well aware of the fact that the song was a regular show-stopping part of The Shadows’ live act and in December 1965, the group were ushered into the Universal studio. In just two takes, they cut their own brattish twist on the track, making a moderate modification by removing all mention of visits to bedrooms in the process. To ameliorate any egos that may have been bruised by this perceived compromise, they were allowed to record an original for the B-side, the brooding, soulful slow burner ‘Dark Side’.

Just as they were readying the recordings for release, record company execs realised that the band bore the same name as the former backing group of British pop star and latter-day child-sex-offence suspect Cliff Richard and thus a new moniker would have to be chosen. A first suggestion – The Tyme – was dismissed out of hand by the band, who feared it might jeopardize the hard-earned fan base they’d developed while working as the Shadows. Just before the distinctive yellow and pink 45 labels were printed, The Shadows Of Knightwas suggested and the group agreed, feeling it had an English ring to it. It was later claimed that it was a mere coincidence that their sports team back in Prospect High School had been known as The Knights!

The record came out right at the end of January ’66 and, spurred on by rabid fans from The Cellar jamming switchboards with requests and countless WLS spins, it soon went supernova, selling over a 100,00 copies within the first 10 days. By April it was a national smash, storming into the Top 10. Its remarkable rise took the tiny Dunwich by surprise, and they found themselves having to stagger releases around the country in a bid to cope with soaring demand. This meant that it peaked in certain markets before it was even released in others, thus impacting negatively upon its weekly chart placement. Also significantly, the song received only minimal airplay in certain less censorious or conservative key markets, such as Miami and California, where Them had only recently topped the charts with the very same track. Ultimately, Dunwich decided to cede distribution to Jerry Wexler and Atlantic, who then facilitated Canadian and British releases.

Boosted by this sudden success, the band started gigging far more widely around Chicago and Illinois and allowed their weekend residency at The Cellar to pass on to local blue-eyed soul act The Mauds, whose name apparently derived from a play on the sound of “mod”, believe it or not, and who were championed early on by Jimy Sohns himself. Around this time the group returned to Universal to cut their debut album, which came out in May and was imaginatively titled Gloria. As it turned out, the recording ended up taking slightly longer than anticipated as various band members, doubtless affected by the harsh northern climate, came down with heavy colds. As Sohns remembers, by the end of it all, the band were left with rather mixed emotions: “We didn’t like our producers very much. They were always trying to stop us from being ourselves and they cut parts that we felt were important out of the final mixes. That said, we were happy with the sales, of course, and you can’t argue with success.”

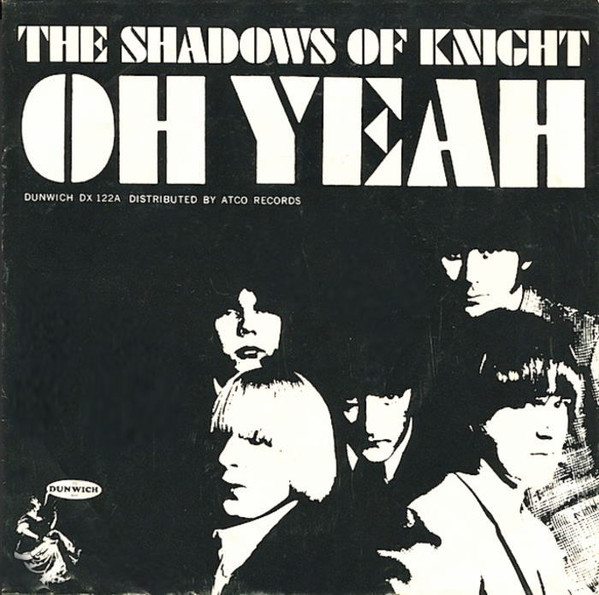

Two tracks from the LP were rushed out as the second 45 and once again Dunwich went for a cover backed by an original. The version of Bo Diddley’s ‘Oh Yeah’ starts out slowly smouldering, with Joe Kelley’s piercing stabbed lead licks threatening to ignite, and then really bursts into life on the intense Yardbirds-style rave-up sections that are pushed along by Warren Rogers’ throbbing bass lines. Even better was the Sohns / Kelley B-side, ‘Light Bulb Blues’ – a furious punk R&B track that features the most perfectly controlled sustain, always on the verge of dissolving into feedback, yet always keeping it together as it hammers through the two and a half minutes. Failing to capture the public imagination quite as effectively as its predecessor, the single peaked nationally at #39, effectively marking the end of the band’s days as coast to coast heroes.

The album itself featured all four sides of the 45s alongside seven other cuts, six of them covers that showed their deep immersion in the electric sounds of black Chicago. Sohns recalls how “we used to sneak in to see Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters when we were real young. Then later on, Otis, James Brown, Wilson Pickett and we also really liked The Chambers Brothers too.”

The years spent soaking up the sinful, soul-drenched local scene are worn proudly on the sleeve. There were no less than three Willie Dixon songs – a gutbucket bludgeoning of ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’ that featured Joe Kelley on blues harp, a cacophonous clattering slash at You Can’t Judge A Book and then the disc closer – a frenetic dash at his ‘I Just Want To Make Love To Yo’u, complete with an explosive pop-art auto-destruction Who-ripped mid-section; there’s then Preston Foster’s ‘I Got My Mojo Working’ performed at a flat-out sprint, a fairly standard mid-tempo take of John Lee Hooker’s Boom Boom and an almost motorik drive through Chuck Berry’s ‘Let It Rock’. The fuzz-laden sole extra original, ‘It Always Happens That Way’, is a standout that leaves you craving an extra serving or two of home-cooked goodness. Make no mistake about it: Gloria is a triumph of youthful chutzpah and verve and in its reappropriation of the British beat groups’ vital reworkings of the deep Chicago roots, it somehow manages to add its own extra local layers.

With two Top 40 singles and a long player under their belt, the band were invited to join Dick Clark’s Caravan Of Stars. Kicking off in Salina, Kansas, the procession then proceeded to hard nose the highway right round the country, packing 35 dates into a 44-day period. A set was usually around 40 minutes long – 12 or 13 songs at best – and also on the tour were the (‘Time Won’t Let Me’) Outsiders, The Seeds, The McCoys and Question Mark & The Mysterians. The Shadows Of Knight’s position on the jaw-dropping, five-band bill varied almost nightly, as Jimy Sohns recalls: “It depended on where we were in the charts at the time, so it’d be anywhere from the middle to the bottom!” Given what you’d imagine the potential for depravity and dementia must’ve been, the singer’s memories of the event seem almost innocent:b“We were all a bunch a characters driven by testosterone. I remember every girl was named Gloria! I didn’t see any drugs on that tour. No drugs for me until ’70! My drug back in ’66 was women.”

The increasingly peripatetic lifestyle was slowly starting to take its own kinds of toll on the group, though, and also resulted in some unusual arrangements. Jimy Sohns again: “I was living at home until I was 50! Well, I was married for three short years, but for most of these years I was on the road. My mom would wash my clothes and I’d take off again.”

Rehearsing and writing were done very much on the hoof, with hotel room sessions occurring organically as well as bashes in the basement of Warren Rogers’ parents’ place. New songs would get trialed in club soundchecks and the writing process was slightly unusual in that drummer Tom Schiffour was also a highly adept guitarist brimming over with ideas for melodies, bridges and the like, whilst the rest of the group all pitched in as well.

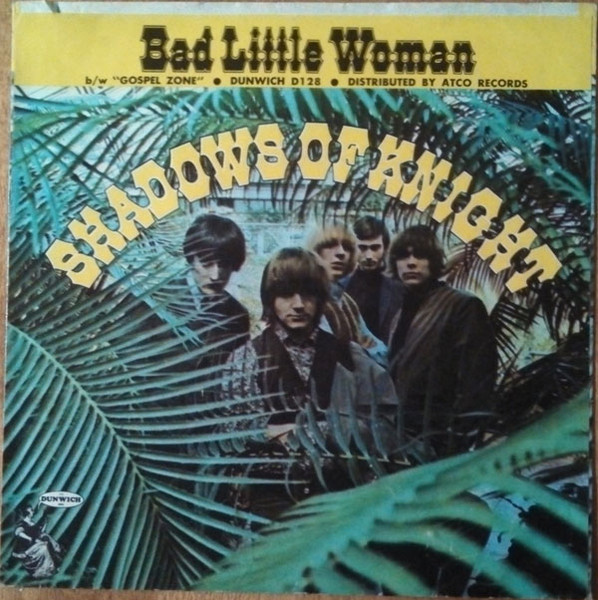

Despite the new songs, the third 45 – released in August – was yet another cover, albeit one from a most unlikely source. Presumably figuring that as Belfast had provided the band with their breakthrough hit, there must be further gold in them there hills, they somehow stumbled upon a track by The Wheels, who’d emerged from the same Maritime Hotel scene as Them, and who’d also opted for their own attempt at Gloria as the A-side of their debut single. Signed to Columbia in the UK, in February ’66 they released one of the all-time great British R&B 45s – ‘Bad Little Woman’ backed with ‘Road Block’. Both sides were bursting with such pent-up frustration and violent energy that they barely held together at the seams, with ‘Road Block’ in particular being a tour de force, stripping ‘Mystic Eyes’ down to a primal volcanic core and grinding it deep into the blood and bones of any listener that encountered it. Unsurprisingly, it bombed and all-but vanished off the face of the earth until it was disinterred by Greg Shaw for the legendary and life-changing (well, for me, at least!) Pebbles Volume 6: The Roots Of Mod.

The Shads, however, plumped for ‘Bad Little Woman’, and amped up the dramatic tension by slowing it down, dispensing with the harmonica and instead bringing an organ (played by newcomer Dave ‘The Hawk’ Wolinski) further to the fore. Joe Kelley was by now starting to hit upon a truly unique guitar sound and style and Sohns just oozed real lust and menace. Predictably perhaps, the Tom Schiffour flip, ‘Gospel Zone’, was even better. The production is fatter and fuller, the guitars crunchier, the Bo Diddley beat no longer just a blatant borrowing, but the foundations of a new and more confident, competent group sound. The track has it all: reverbed hand claps, clattering chords teetering on the edge of chaos, and the bass and drums in the kind of lockdown that Brussels can only dream of. How could it not be a smash? It crawled into the Top 100, peaked at number #91 and from there slid meekly off into the bargain bins. Who said life was gonna be fair?

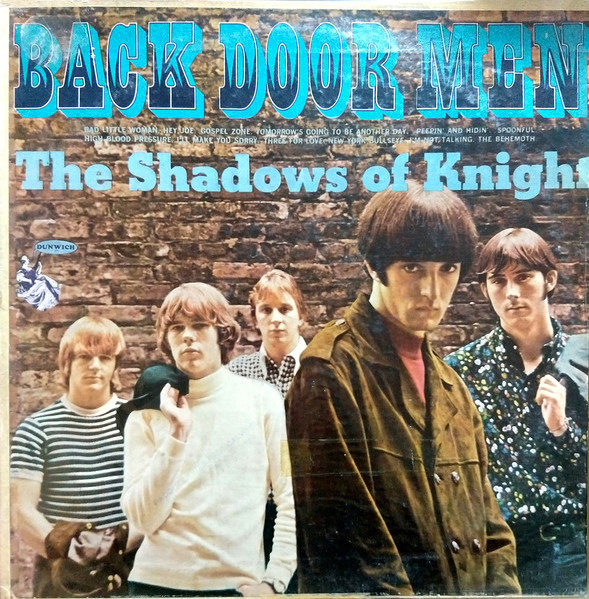

This disappointing chart performance didn’t deter the band from laying down a second LP, Back Door Men, which saw the light of day in the autumn of the year, and which captures a rapidly maturing band who nevertheless retain their balls and their aggression. The obligatory blues covers are still there – a bog standard bar-room romp through Jimmy Reed’s ‘Peepin’ and Hidin’’ which features that slightly embarrassing vocal thing young white men do when attempting to sound much older and blacker than they are, and yet another Willie Dixon track, a perfectly respectable reading of Spoonful, but one which pales into insignificance when set against such devastating versions as Q’65’s. Far better was Tommy Hart’s ‘Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day’, covered as a pleasant enough beat pop track around the same time by The Monkees, but here delivered as a dancefloor-friendly garage soul blaster. The folk rock wave was also clearly having an impact, with Joe Kelly’s ‘Three For Love’ sounding for all the world like an early Beau Brummels demo. However, it was one of two Harry Pye songs that really pointed a way forward. ‘The Behemoth’ is a dense raga-rock exploration that, while perhaps less focused than it could have been, still hinted at other worlds, ones where the likes of The Mystic Tide would take post-surf fret frenzy to the Orient and then beyond.

To coincide with the album’s release, the band’s fourth, final and finest 45 of the year was also offered up. ‘I’m Gonna make You Mine’ is, quite simply, one of the best records ever recorded. As good as ‘Great Balls Of Fire’, ‘My Generation’ or ‘Teenage Kicks’, it’s a swaggering, primal rush of hedonism, hormones, adrenaline and arrogance. Remarkably, the Kelly flip, ‘I’ll Make You Sorry’, also included on the LP, is almost as incredible. As the year drew to a close, the group were at some kind of creative zenith and yet just as they were peaking, the long slide downhill suddenly started to make itself apparent.

In November, the spectre of the draft that hung over every young American’s head loomed fully into view, snatching Warren Rogers away – forever. “He didn’t see frontline action, as far as I know,” recalls Jimy Sohns, “but contact was lost with him immediately – and ever since.” To fill the gaping hole this left, Dave Wolinski – ‘The Hawk’ – moved from augmented organ duties to a full-time post as bassist. ‘I’m Gonna Make You Mine’ allegedly sold 100,000 copies within a fortnight of its release, but then stalled at number #89 in the hit parade, as ironically, given their entry point into the whole shebang, it had fallen foul of radio guidelines due to its suggestive lyrics (“I’m gonna take, girl and you – you’re gonna give”).

Amidst such annoyances, musical differences were starting to undermine band unity, with Joe Kelly wanting to delve deeper into his blues fixation, while Jerry McGeorge felt the chimes of folk-rock tugging at his sleeve. To further add to the rising storm, Dunwich were also starting to struggle, finding themselves unable to replicate The Shadows Of Knight’s success with any of their other 30-plus releases. Sohns looks back in anger at this time of all things ending: “We were playing so much that it was hard to realise we were being grossly mishandled by our production and management, who were the same people anyway.”

As ’67 beckoned, the group were more or less at the end of their tether. Sure, there’d be another couple of 45s – and a preposterous potato chip-promoting flexi that was so far removed from the zeitgeist it may as well have been found in a time capsule, yet within a few short months Traut and Badonsky would have given up the ghost with both the label and the band, eventually apparently selling all their masters to the main distributor, Atlantic records, for the nominal – and preposterous – sum of one dollar.

McGeorge soon jumped ship and appeared on the fine debut LP by another Traut / Badonsky act, HP Lovecraft (see what they did there!), while Kelley and Schiffour wound up forming The Joe Kelley Blues Band. Schiffour later ended up in The Bangor Flying Circus, alongside The Hawk. Jimy Sohns, against all odds, somehow stuck to his guns and recruited a whole new band, signed up with Kasnetz-Katz, cut the million-selling club classic ‘Shake’ and a wildly underrated third LP. He sadly died aged 75 in July 2022

That marvellous third album is a story we will save for another day

Special thanks to Jimy Sohns and Brian Hogg, without whose assistance this piece could never have been written.

This article ran in issue #53. Order now to read the full feature.

Subscribe to Shindig! here to read many more articles like this in our 100 page monthly print magazine