Concerning Hippies – Counter-Cultural musings from TSPTR. Dossier #6

In the sixth of our monthly counter-cultural musings from TSPTR, we look at the hippie fixation with Lord Of The Rings and Tolkien’s own innate radicalism

In 1978 J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord Of the Rings was brought to the big screen by the anarcho-independent animator Ralph Bakshi. Previously most well-known for his production of Robert Crumb’s Fritz The Cat, billed as the world’s first XXX animation, Bakshi interpreted Tolkien’s dark fantasy into a nightmarish rotoscoped acid flashback that pulled no punches. This wasn’t however the first time that Tolkien’s masterwork had found its way into favour with the counterculture.

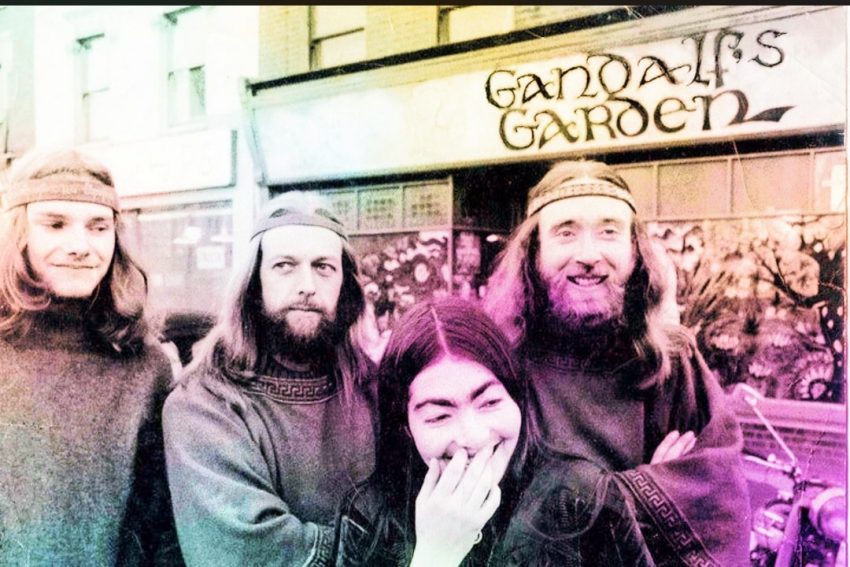

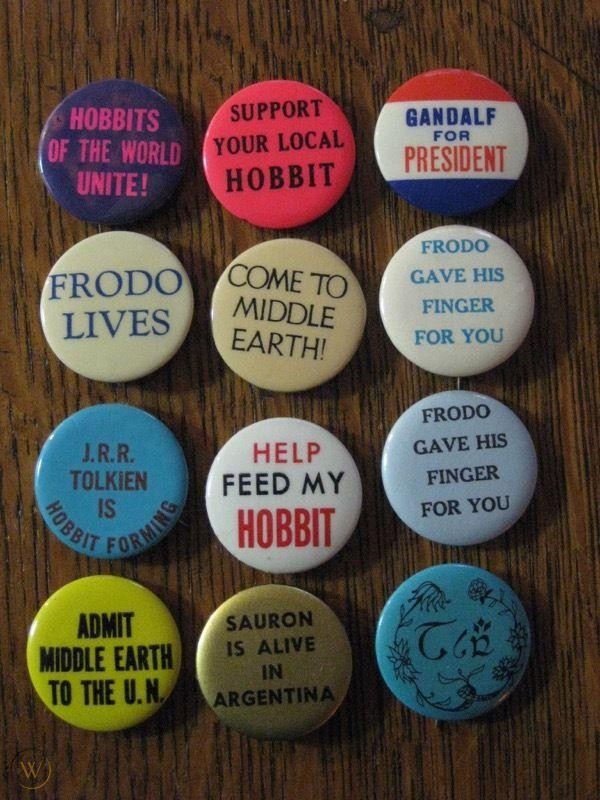

During the ’60s, the church-going Tolkien was bemused to learn that many of his first American fans were pot-smoking, free-loving hippies. These hippies pointed to the novelist’s love for trees and hatred of the ugly side of industrialism as proof of their simpatico outlook. Some of the most prominent agents of change in the counterculture — that is, musicians — were also fans of Tolkien’s work. The Beatles wanted to film a live action version of the books with The Fab Four as the hobbits. Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Genesis, Rush and Pink Floyd all wrote songs involving Tolkien mythology. The words “Frodo Lives” and “Gandalf For President!” were spray-painted on walls, printed on shirts and buttons, and shouted through loudspeakers — memes before memes were a thing. In the UK, a mystical community named Gandalf’s Garden flourished at the end of the ’60s as part of the London hippie/underground movement, running a shop and a magazine of the same name. They advocated the spiritual aspect of hippie life and served to connect people in London and around the world who were looking for an alternative to the dreary and destructive realities of industrialization, war, or even the darker aspects of the “turned on” life.

Tolkien has often been dismissed as a hopelessly old-fashioned dead white male conservative, while others have portrayed him as the soft-edged moderate due to his love of nature, however it’s fair to say that Tolkien’s political views were anything but moderate. An early hint of this can be found in the beloved homeland of the Hobbits, the Shire. Its pastoral villages have no department of unmotorised vehicles, no internal revenue service, no government official telling people who may and may not have laying hens in their backyards, no government schools lining up hobbit children in geometric rows to teach regimented behaviour and groupthink, no government-controlled currency, and no political institution even capable of collecting tariffs on foreign goods.“The Shire at this time had hardly any ‘government’. Families for the most part managed their own affairs.”During Tolkien’s formative years, cars and combustion engines invaded life’s every nook and cranny; mechanics and scientists threw flying contraptions into the sky in order to rain destruction upon people; the tally of the dead neared 100 million from just two global conflicts; the natural resources mined and harvested to feed this combat; the nuclear bomb. These factors powerfully influenced Tolkien’s writing, and his characters deal with deep confusion, a sense of loss, and an unsteady grip in a changing world they no longer understand. Early in his quest to destroy “The One Ring”, before Frodo truly had any idea of what he had gotten himself into, Frodo asks the lady Goldberry if Tom Bombadil owned the woods they were walking through. She corrects him, saying “The trees and the grasses and all things growing or living in the land belong each to themselves.”

Tolkien has often been dismissed as a hopelessly old-fashioned dead white male conservative, while others have portrayed him as the soft-edged moderate due to his love of nature, however it’s fair to say that Tolkien’s political views were anything but moderate. An early hint of this can be found in the beloved homeland of the Hobbits, the Shire. Its pastoral villages have no department of unmotorised vehicles, no internal revenue service, no government official telling people who may and may not have laying hens in their backyards, no government schools lining up hobbit children in geometric rows to teach regimented behaviour and groupthink, no government-controlled currency, and no political institution even capable of collecting tariffs on foreign goods.“The Shire at this time had hardly any ‘government’. Families for the most part managed their own affairs.”During Tolkien’s formative years, cars and combustion engines invaded life’s every nook and cranny; mechanics and scientists threw flying contraptions into the sky in order to rain destruction upon people; the tally of the dead neared 100 million from just two global conflicts; the natural resources mined and harvested to feed this combat; the nuclear bomb. These factors powerfully influenced Tolkien’s writing, and his characters deal with deep confusion, a sense of loss, and an unsteady grip in a changing world they no longer understand. Early in his quest to destroy “The One Ring”, before Frodo truly had any idea of what he had gotten himself into, Frodo asks the lady Goldberry if Tom Bombadil owned the woods they were walking through. She corrects him, saying “The trees and the grasses and all things growing or living in the land belong each to themselves.”

Significantly, Tolkien once described himself as a hobbit “in all but size”, commenting in the same letter that his “political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy”. As he explained, “The most improper job of any man, even saints, is bossing other men. Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity.” In the Shire, Tolkien created a society after his own heart, one marked by minimal government, private charity, and a commitment to property rights and the rule of law. This isn’t to say the Shire is without problems. Near the end of the third book, Frodo returns home after a quest to the destroy the corrupting ring of power. To his dismay, a gang of bossy outsiders has infiltrated the Shire, “gatherers and sharers… going around counting and measuring and taking off to storage”, supposedly “for fair distribution”, but what becomes of most of it is anyone’s guess.

Conservatives and progressives alike also have seen in it a pointed critique of the modern, hyper-regulated nanny state. Ugly new buildings are being thrown up, beautiful hobbit homes spoiled. And for all the effort to “spread the wealth around” (to borrow a phrase from a former president), the only thing that seems to be spreading is the gatherers’ power. It’s a critique of aesthetically impoverished urban development, to be sure. In fact, the Shire’s joyless regime of bureaucratic rules and suffocating redistribution owed much to the drabness, bleakness and bureaucratic regulation of post-war Britain under the Attlee Labour government.

There is, in this back-to-basics sort of way, a sense of relatively harmless nostalgia embedded throughout The Lord Of The Rings, giving readers in the ’60s and ’70s an escape from the strife of their time — strife that was directly visible on a daily basis for the first time in history, due to the advent of the television and Technicolor. This nostalgia inspired longing for a return to life before strife caused by the divisive lust for resources – i.e., colonisation, industrialisation, the traditional Western understanding of how the world worked. Yet part of the success and allure of The Lord Of The Rings was that it did not let readers off the hook completely; it was not pure escapism. A sense of mission and drive pervades the books, and the ways in which it was relatable to readers in the advent of counterculture movements meant that the causes Tolkien advocated for were easily transposed onto their minds, thus becoming important to them.

In Robert Hunter’s recounting of the origins of Greenpeace, The Greenpeace To Amchitka: An Environmental Odyssey, he discusses their inaugural environmental protest effort and the journey to Amchitka to protest the nuclear test sites there: “We are on our way to the dread dark land of Mordor, and Amchitka is Mount Doom… somehow we have to hurl the Ring of Power into the fire and bring down the whole kingdom of the Dark Lord.”

Their organisation’s love for Tolkien’s work survives to this day, sometimes in the form of amusing advertisements, but it wasn’t just Greenpeace who found meaning in The Lord Of The Rings. Also appealing to the burgeoning anti-war, feminist and civil rights movement activists was Tolkien’s political subtext of the Hobbits, and their wizard ally, leading a revolution. The military industrial complex targeted by protestors resembled Mordor in its mechanised, impersonal approach to an unpopular war. When he is drafted into bearing the Ring to Mount Doom, Frodo feels an “overwhelming longing to rest and remain at peace… in Rivendell”. Those who led the fight against Sauron’s army stood reluctantly, hoping this would be the “War To End All Wars”.

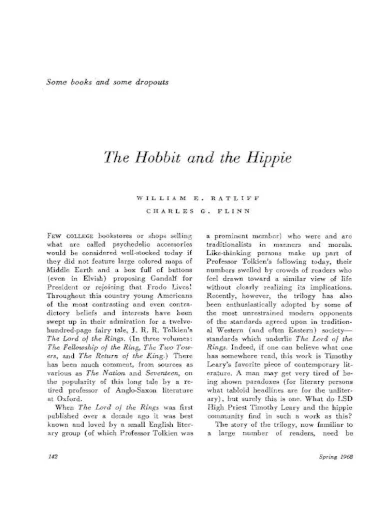

In spring ’68, environmentalists William E. Ratliff and Charles G. Flinn attempted to illustrate the connections between The Lord Of The Rings and counterculture, authoring an article titled ‘The Hobbit and the Hippie’. They summed it up perfectly: “When The Lord Of The Rings was first published over a decade ago it was best known and loved by a small English literary group (of which Professor Tolkien was a prominent member) who were traditionalists in manners and morals… Recently, however, the trilogy has been enthusiastically adopted by some of the most unrestrained modern opponents of the standards agreed upon in traditional Western (and often Eastern) society. There is a mature acceptance of the necessity of fighting the evil, even by the use of force. This is not an expectation that any particular effort of their own will finally conquer the evil but a recognition of a present duty.”

In spring ’68, environmentalists William E. Ratliff and Charles G. Flinn attempted to illustrate the connections between The Lord Of The Rings and counterculture, authoring an article titled ‘The Hobbit and the Hippie’. They summed it up perfectly: “When The Lord Of The Rings was first published over a decade ago it was best known and loved by a small English literary group (of which Professor Tolkien was a prominent member) who were traditionalists in manners and morals… Recently, however, the trilogy has been enthusiastically adopted by some of the most unrestrained modern opponents of the standards agreed upon in traditional Western (and often Eastern) society. There is a mature acceptance of the necessity of fighting the evil, even by the use of force. This is not an expectation that any particular effort of their own will finally conquer the evil but a recognition of a present duty.”

This is the essence of counterculture, and of environmental work: No single person expects that they can save the world all on their own. We as a species are responsible for the planet because we are part of it, not separate from or above it. And, finally, it is the ordinary people, the hobbits, the smallest of the Free Folk, who make all the difference.

The subject of greed also featured high on Tolkien’s agenda, especially in The Hobbit, a greedy dragon, a greedy businessman, greedy dwarves, if you assume capitalism is based on greed, then you might see in this a critique of economic freedom. But look more closely. The greedy dragon Smaug and his enemies the dwarves aren’t entrepreneurial capitalists but misers. They don’t risk and invest; they hoard.

As for the greedy businessman we meet when Bilbo and the dwarves reach Lake-town, notice that this businessman is also the mayor of Lake-town. He’s cronyism personified. He’s gamed the system to give himself artificial advantages in the marketplace – hardly the definition of a free economy. In the final third of The Hobbit, greed and miserliness all but shut down trade and human flourishing in the river valley. When they are displaced by generosity and trust, thanks in no small measure to the courage and generosity of Bilbo and Gandalf, enterprise and trade expand in the river valley. Thus does Tolkien’s story capture what some have missed? That the essence of a free and flourishing economy are not greed and selfishness but rather freedom, creativity, courage, and trust.

The intellectual establishment of Tolkien’s day hated God and loved Big Brother. The Catholic Tolkien loved God and hated Big Brother. Unlike the many self-appointed “radicals” in lockstep with the socialist spirit of his age, Tolkien was the true radical – the round peg in the square hole of modernity. The issue of Tolkien’s political vision is rich and complex. But there’s a line running through all that nuance that isn’t the least complex. How would Bilbo Baggins and his maker vote? For far smaller government, and tea and pipeweed at four – in a hole in the ground there lived an enemy of big government.