The Neil Young Official Bootleg Series – Carnegie Hall 1970

HARVEY KUBERNIK dives into the new archival NEIL YOUNG set, released this Friday, bolstering the information with quotes from many of his interviews

Over Neil Young’s career, a few special shows have earned an almost mythic reputation, thanks to the dubious but nevertheless appreciated (in retrospect) practice of bootlegging.

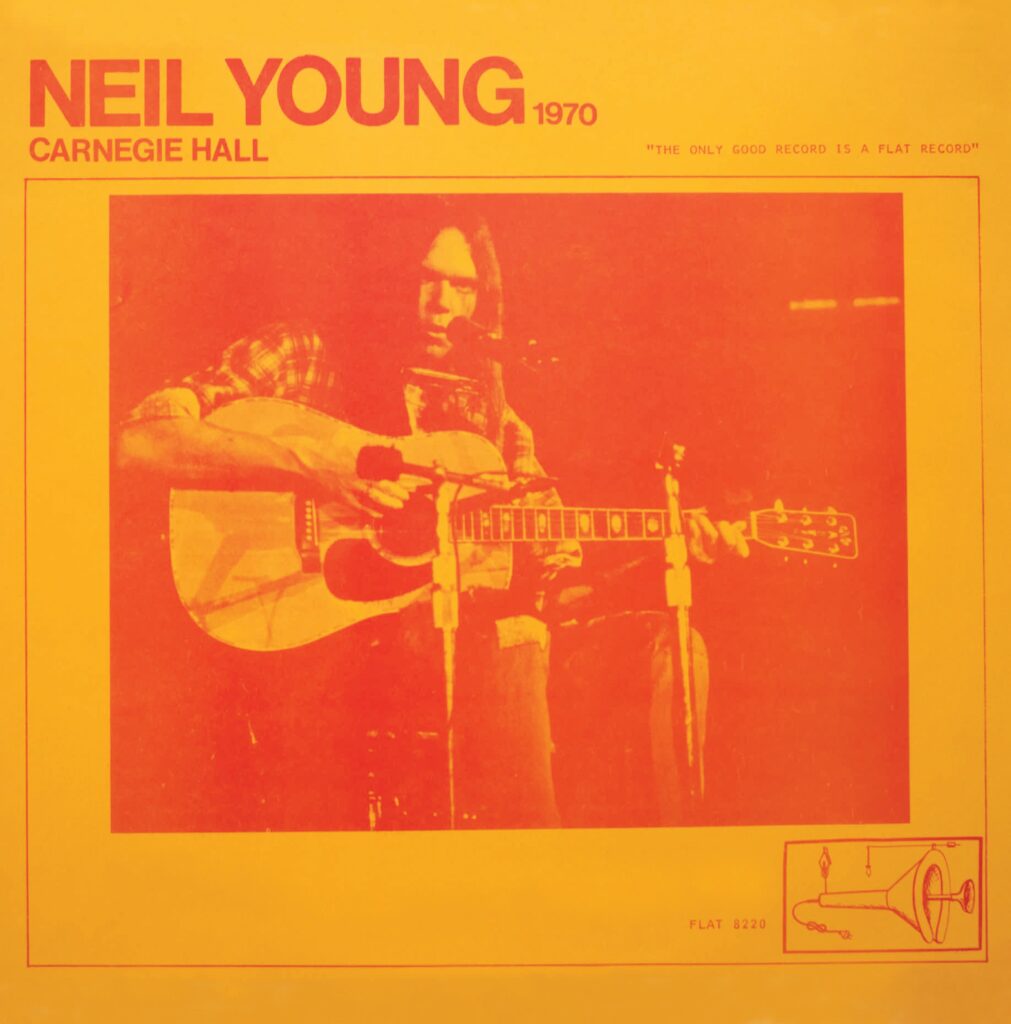

Shakey Pictures Records and Reprise Records are now happy to announce the first of a new series – The Neil Young Official Bootleg Series – Carnegie Hall 1970, available on double vinyl, double CD and High Res Digital on Friday, 1st October.

This recording was made from the show on 4th December, 1970 and it was the first time Neil ever walked onstage at Carnegie Hall. There were two shows at Carnegie Hall, one on the 4th and one followed at Midnight the next morning. No bootleggers ever captured this first show, and it was, by far, a much superior show according to Young.

On his Neil Young Archives website during 18th August, Young wrote, “This first performance has never been heard. We recorded this great concert in high res analogue as it was going down. Bootlegs of the second show have been floating around for years, but never this – the very first show! It’s raw and real!”

The concert’s generous set list covers one of the most revered eras of Young’s career, with stripped-down versions of the tunes ‘Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere’, ‘Down By the River’, ‘Helpless’ and ‘Sugar Mountain’” plus ‘After the Goldrush’, from the album of the same name, released only nine weeks prior to the Carnegie Hall show. Neil even plays the poignant songs ‘Bad Fog Of Loneliness’, ‘Old Man’ and ‘See The Sky About To Rain’ before they were recorded and released.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-BrD51uKbh8

1. Down By the River

2. Cinnamon Girl

3. I Am a Child

4. Expecting to Fly

5. The Loner

6. Wonderin’

7. Helpless

8. Southern Man

9. Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing

10. Sugar Mountain

11. On the Way Home

12. Tell Me Why

13. Only Love Can Break Your Heart

14. Old Man

15. After the Gold Rush

16. Flying on the Ground is Wrong

17. Cowgirl in the Sand

18. Don’t Let it Bring You Down

19. Birds

In December ’70, Neil was in LA resting with a bad back at The Chateau Marmont on Sunset Boulevard when the next major love of his life arrived. LA actress Carrie Snodgress had ridden the pop-cultural zeitgeist to ‘It Girl’ status with her memorable performance in the Frank Perry movie Diary Of A Mad Housewife.

Neil had read a magazine feature about her and been immediately captivated. When he found out Carrie was in town, performing in a theatrical production in downtown LA at The Mark Taper Forum, Neil tracked down her number, called her up, or had an associate or road manager invite her to visit an ailing rock star in his time of need.

Neil, with Carrie in the house, delivered a solo recital at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in the LA Music Center on 1st February, ’71.

I worked a double-shift at the West LA College library to earn the money for my ticket. I sat near actor Dean Stockwell and dancer/actress and singer Toni Basil.

The roots of this stellar live Carnegie album go back to Young’s tunes in Buffalo Springfield.

The album, Buffalo Springfield Again began in ’67. Shortly afterwards, Young’s friend and drummer/record producer Denny Bruce visited Neil’s cabin in Laurel Canyon. Denny had introduced Neil to arranger/producer/songwriter Jack Nitzsche in ’67 at the Charlie Greene and Brian Stone management office in Hollywood. “Neil had his jumbo acoustic 12-string guitar and he’s halfway through a song that turned out to be ‘Expecting To Fly’, Bruce explained to me in a 2014 interview.

“There was always a different tuning and Neil was also really good t using various time changes. Then Neil starts talking about ‘Expecting to Fly’ and said, ‘I hear it as a song for The Everly Brothers.’ I agreed and mentioned the song to Jack Nitzsche, who was about to work with The Everly Brothers. Jack and I went over to Neil’s place and he played ‘Expecting to Fly.’ Then Jack said, “Never mind the Everlys. This is for Neil Young. We can make a great record.’

“Neil now had confidence building from Jack and Gracia Nitzsche, and myself. Jack really believed in Neil’s music. Jack knew Neil would eventually become a solo star. He knew he wasn’t meant to be in a band.”

Jack subsequently brought Neil Young to the attention of Mo Ostin at Reprise Records. Nitzsche’s keyboard work informed and enhanced Young’s debut solo LP.

“Neil was the beginning of art-rock to me,” Jack stressed in a 2000 interview we did. “You know, when I was part of the band Crazy Horse. I sort of took over and became the producer and made Crazy Horse sound much better than they actually were. I was on tour them years ago, Neil Young and Crazy Horse. Miles Davis opened for us at the Filmore East. I thought it was an insult to Miles…”

“Jack Nitzsche called me to play keyboard on some dates in 1967 at Sunset Sound studio” recalled keyboardist/arranger Don Randi in a 2015 interview we conducted.

“Bruce Botnick was the engineer. When I walked into the studio I didn’t realise it was for Buffalo Springfield. I thought it was for a Neil Young album, because he was supposed to be breaking away and going on his own. Hal Blaine and Jim Horn are on the track. I played piano and organ.

“I’m on “Expecting To Fly” with Russ Titelman, Carol Kaye, and Jim Gordon. I had some little head chart arrangement to work from and another of the tunes might have been sketched. It was pretty wide open with the chord changes. And all you had to do was hear Neil sing it down with an acoustic guitar and you sat there, ‘Oh my goodness…’

“Jack and I never judged artists by their voices. To me it didn’t matter ‘cause I loved the music so much and Neil was able to sell it. There are some people you can’t stand them on record until you see them live. And once you see them live you can understand their records. That doesn’t happen a lot. But it does happen.

“And I would love to have said how big Neil was gonna get. I don’t think he realised it. But I loved Neil’s music. Goodness gracious. This guy’s writing… I thought everybody and their mother was gonna try and start doing his songs. I knew he was a songwriter. Some of the tunes were movies. They were scripts. To me, Neil was like another [Bob] Dylan. That’s what he reminded me of. He could do Dylan but I think he did Dylan his way. It was Neil Young. It wasn’t Bob Dylan,” Randi reinforced.

“Look, I’ve been on dates with Elvis [Presley] and [Frank] Sinatra, guys who would arrive with an entourage. Neil would show up by himself. You have to realise that as great as a musician and as great as a songwriter he is, Neil would also realise talent himself. He realised a sound that he liked from a guitar. Neil knew that the only way to get it was to have that guitar. You’re not gonna get that off a Tele. You’re not gonna get it off something else. Neil was smart enough, and most of the good writers and players, if they didn’t have the acoustic guitar they went to that kind of guitar. Neil liked to experiment. And he would say, ‘Oh my goodness. Why don’t I do that?’ And he had the wherewithal and had the time. He had the time to take his time. ‘Wow. That’s a real nice sound. I like this. I don’t like that.’

“Neil was smart enough to know what he wanted and knew how to get it. And, Neil had Ahmet Ertegun and Atlantic [Atco] in his corner. Ahmet had some of the music publishing [Cotillion Music] on Neil’s debut LP. Ahmet encouraged the guys in Buffalo Springfield to write and do demos at Gold Star. I lived at Gold Star throughout the entire ’60s. Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun were two of the smartest people in the record business. They almost signed me to Atlantic.

“You have to realise that as great a musician and as great a songwriter as he is Neil would also realise talent himself. Neil liked to experiment. He was smart enough to know what he wanted and knew how to get it. Neil wrote cinematically and Jack arranged cinematically. I loved Neil’s music. Some of the tunes were movies. They were scripts.”

“Sometime in 1969, maybe I was in LA. living at my grandmother’s,” singer/songwriter and Moby Grape co-founder Peter Lewis reminisced to me in a 2015 interview.

“I was at Wallichs Music City in Hollywood inside a listening booth and spinning Neil’s first solo LP and Skip Spence’s Oar album. I was driving around in my Volkswagen bus and this chick Lorraine pulls up next to me in a big Lincoln who eventually married Dave Mason. And I became a friend of his. I earlier met her in Hawaii when I went to see Rick Nelson play. She had gone to Westlake School For Girls and a band I had would play there.

“She (now) had a house in Topanga Canyon. So Lorraine says, ’Let’s go visit Neil Young.’ Moby Grape knew Neil and Buffalo Springfield from shows together and studios. We go to his house. I don’t know where the fuck it is. She rings the buzzer and says ‘It’s Peter Lewis.’ Neil answers. He opens the door and kind of peaks out. ‘Hey man! Come on up!’ Neil is with his wife Susan. He had just got married and was happy to see me. He played us the acetate of Everybody Knows This Is No Where. I flipped out and told him, ‘You‘re gonna be a huge rock star.’

“What I saw what was goin’ on with Neil at that moment, honest to God’s truth, is like a rivalry with Stephen Stills where he could never do what he really wanted to as long as he was that band Buffalo Springfield. Okay. When he played it for me he had a big wooden chair he was sitting in. And he spun the acetate. It hadn’t been released yet’ ‘Cinnamon Girl’ and ‘Down By the River.’ I’m comparing it to his first record. And I told him what I thought about it. ‘But this is just gonna make you a huge rock star, man. Because you finally got that sound that you were lookin’ for. It’s not Brian Hyland and it’s not ‘Jack Nitzsche’s take on you.’ You did this.’ And he got guys that did what he told them to fuckin’ do. That’s what he wanted and Buffalo Springfield would not do that. I think we went into the kitchen and he wanted to jam but I wasn’t in a jamming space.”

‘Cinnamon Girl’ is heard on Young’s Carnegie Hall 1970. SiriusXM deejay, Rodney Bingenheimer, in his ’69 music column for GO “the world’s largest circulation of any pop weekly,” was the first to tout ‘Cinnamon Girl’ in print, after receiving a promotional test pressing from Pete Johnson at Reprise/Warner Bros. Records.

In 2015 I wrote Neil Young Heart Of Gold, currently published in six foreign language editions. I did a series of interviews with Dr. James Cushing, a deejay on KEBF-FM in Morro Bay, CA.

We discussed Young’s ’67-70 recorded catalog.

“Neil, early on his in career, could take his Gold Star, Sunset Sound or Columbia studios recorded material, with Buffalo Springfield and his first solo LP, selections like ‘Broken Arrow’, ‘Expecting To Fly,’ ‘Last Trip To Tulsa,’ and could transfer them quite effectively to solo platform from the initial context of a band. It shows essentially that they are folk songs, which is the strength and is rooted in something. And that music is rooted in Scottish or Celtic. This is something he has in common with Bob Dylan. The chord changes, the structure of them. They’re very skillfully put together in the same way folk songs are put together.”

We examined Buffalo Springfield’s Last Time Around album. Some of the tracks are done acoustically in this Carnegie Hall endeavor.

“I’ve heard Neil is a bit distant from it or sees the album as a contractual collection of individual recordings by group members. But it has his ‘I Am a Child’ and ‘On The Way Home!’ I think those two might be Neil Young’s first two masterpieces.

“‘I Am A Child’ and ‘On The Way Home’ first shows those strengths that stand out during the rest of his career. Evidence, a willingness to be as open, naked and vulnerable in ‘I Am A Child’ as possible to bravely go against the macho rock stereotype and come off as someone who was willing to lead with his vulnerability.

“One of the virtues that Neil Young’s music represents was the willingness to expose one’s emotional vulnerability. As a survivor of polio and an epileptic, Neil Young had already been through the pain the traditional and new underground media were covering.

“He and Joni Mitchell experienced physical disease, immobility, and confinement, all things that tend to make you stand out from other groups of kids and make you more sensitive and aware,” Cushing suggested.

“Mitchell contracted polio in’53 and suffered more severely, including some paralysis. It’s important not to be reductive and say, ‘Oh, they suffered from polio, Neil had a slew of epileptic seizures. Therefore they understand the plight.’ Their art is a lot more interesting than that. The times required artists able to give convincing musical form to the new inwardness that resulted from the collapse of the ’60s ideals. Mitchell’s and Young’s music dramatised how people as individuals could pull through dark times. Their Hollywood-birthed albums of ’68 illustrate this.

“‘Sugar Mountain’ isn’t my favourite Neil Young song but it’s the one I think about most often,” admits Cushing.

“Neil Young’s voice. That high kind of alto tenor with just enough of that Canadian accent, especially with words that end in “R”. ‘Sugar Mountain,’ for example. When we hear Neil for the first time, particularly when he embarked on a solo career, his voice was rather high and plaintive. And so a lot of people didn’t like his voice because it sounded to them whiny and irritating. But his voice stood out at the time because so many alpha males were trying to rock and be macho. And Neil gets extra points for never trying to sound like anybody except his Ontario Prairie self. And we might faintly hear the impact of childhood polio he had in Canada coupled with a family divorce in the early ’60s that possibly informs his vulnerable outsider stance.

“He did write a song called ‘The Loner’. So as a product of a divorced family that circumstance, polio, and bouts with epilepsy, including incidents on stage with Buffalo Springfield, have influence on. And the fact that Neil’s father was a successful writer, Scott Young, also had to make an impression, particularly on a son who winds up using words to communicate to a large audience the songs he’s written. It’s got to.

“The Loner’ has a great riff and the song and record illuminates the main problems with the first album, which is a general failure to rock. ‘The Loner’ is really good. Neil Young’s voice does take some getting used to but once you’ve gotten used to it, it will always be a part of the way you hear some certain range of human emotions.”

On Carnegie Hall 1970, ‘Down By The River’ kicks off the action.

‘Down By the River’ is Neil’s answer to ‘Hey Joe’,” underlines James. “It’s from Joe’s point of view. It’s John Ford and Howard Hawks directing a pop song. I feel it in connection with a western re-telling of a classic murder ballad kind of thing that goes all the way back to the 16th century. ‘Tom Dooley’, ‘Man Of Constant Sorrow’, ‘Hey Joe’, which is a murder ballad. All of these murder ballads are confessions by a stunned and emotionally over-whelmed man who realises he has murdered the one that he loves. And emotionally destroyed by it. In ‘Hey Joe’ it’s a third person thing. But in ‘Down By the River’ on the original Crazy Horse recording there is the sense that the emotional issues in the song are in some way being worked out by the guitar jams. Danny Whitten and Neil Young playing together.

“There is something about the way that feels that is being worked out. You could make an argument that this record, and ‘Cowgirl In the Sand,’ remains the essential Neil Young sound. Although one could make an argument for The Stray Gators. ‘Cowgirl In The Sand’ is not a murder ballad. It’s a kind of prayer to a goddess and the terms of the prayer are being discovered as its being offered. But I might be the wrong gender to fully answer the question.

“Neil Young’s career does have highs and lows. But the highs and lows are there because he has consistently shown a pattern of wanting to experiment and wanting to try new things and wanting to remain in a state of becoming. Rather than a state of being.

“I marvel at Neil Young’s career,” concluded Cushing. “His songs are so powerfully and simply constructed. They seem to have been discovered rather than written. His guitar playing has that marvelously rough-hewn rock out quality that nothing else quite has. His voice is unique. Even though he’s not a blues guy, the interiority and the momentum of his best music is everything what rock was designed to deliver. And his calm and beautiful folk songs are emotionally effecting on an almost pre-verbally deep level. He’s just like Bob Dylan and nothing like Bob Dylan.”

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, includingCanyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop, And Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For November 2021 the duo has written Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Childfor the publisher.

I Appreciate, thanks for your article