No Ordinary Guy – An Interview with Latin soul legend Joe Bataan

JOE BATAAN was a self-proclaimed bad boy turned good. He emerged from the streets of East Harlem to become a star in the ’60s for the fledgling Fania Records label and onto Salsoul in the ’70s. Shindig! met Joe for a characteristically engaging look back over those early days to commemorate the release of a new box set compilation called It’s A Good, Good Feeling: The Latin Soul Of Fania Records (The Singles) out now on Craft.

There’s also a fantastic article in issue #120. Pre -order now.

Shindig!: What was New York like for you growing up?

Joe Bataan: New York was like a melting pot. Because we didn’t have Internet and social media, most of everything was carried by word of mouth or whatever we got on the radio. Growing up at that time, we played and emulated what we heard from others.

In my particular era there was R&B and then along came rock ’n’ roll in 1957 with Alan Freed and then we went into the ’60s. Then a strange thing happened. Of course, the boogaloo originated in Chicago but it caught on in New York..

Ricardo Ray, Pete Rodriguez, Johnny Colon all started out with this new sound they called it boogaloo. It started with some lyrics in English and it caught on. Started to be a dance craze in New York with the young Latinos from El Barrio, Spanish Harlem and it then just caught fire all through the state and spread through the tri-state area.

I got wind of it at that time, and I think my insertion into that type of music was just a little different. I grew up from a doo-wop perspective, so it was easy for me to sing in English not being of the Spanish heritage but having learnt to speak Spanish in the streets of New York, because most of my friends were Latino.

In my trial and error of fiddling with the boogaloo, it was right down my alley. I was able to sing in English and then I found out the secret of doing the cha cha and inserting these lyrics. It became instant gratification to a lot of young fans. I think the difference with me and the other artists is that most of my songs had a story.

I think because of my lyrics they have endured for over 50 years and because I insert ballads also with the boogaloo from that era, it enhanced my popularity until this day and I thank God I’m still able to perform.

The boogaloo had a short life, so I changed my style of play from boogaloo to Latin soul. That was like a brainwave of mine knowing that the word boogaloo sounded too bubblegum and it wouldn’t last throughout but Latin soul would last forever. Because there’s always Latin, there’s always soul. I took that moniker and I’ve been known as the forefront of Latin soul for some time.

SD!: What impact did it Boogaloo have on a younger generation?

JB: Most of the era of Latin music was always done in Spanish and with the upcoming new generation of Spanish speaking kids. Mostly they spoke English and they stopped listening to their parents’ music and they wanted something of their own. The boogaloo came on just about the right time because they could associate the Latin beat with the English verse, because now they were more Americanised living in the United States and growing up in El Barrio so this made it easy for that generation to embrace this music. Just like they embraced The Beatles or the Twist with Chubby Checker. They embraced the boogaloo and they were like wow, this belongs to me. All Latinos. Of course there were blacks also involved in the boogaloo so it became very popular.

My intake into it was that my mother is African American and my father is Filipino. But that put me in the middle, having looked like Latino for all my life. The argument was that, well, Joe Bataan must be Latino. They said no, he’s not. He’s African American. The argument went on for years and of course, to me it didn’t matter. I didn’t grow up that way. I grew up as a human being and of course that reflects in my music. It wasn’t until I was looking for my identity and recorded an album called Afro Filipino that people started to wonder. Well, Gee, who is this guy?

When I was inducted into the Smithsonian when it started in 2010, they made a remark that I was a bridge between several cultures. I was a bridge to the Asian community. I was a bridge to the Latino community and I was a bridge to the Black community. So that was really gratifying. I never had the sense of where I belonged until then, you know, that I really belong to the world.

SD!: When did you first catch the music bug?

JB: As a youngster, we grew up listening to the radio. Most of the radio at that time was Anglo music. Patti Page, Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, etc. So that was my first love because that’s what we were exposed to. You know there wasn’t black radio back in the early ’40s or the ’50s and there was no Latino radio and if there was, it was always at the end of the dial where the signal wasn’t strong enough to be heard.

Finally, when we finally got WINS and Alan Freed after the ’50s, it was something new to us. We had never heard that having grown up on Patti Page, Frank Sinatra, Johnny Ray, and such pop Anglo music. This was new to us. It felt like it was something that belonged to the youth of America at that time, and on that we gradually incorporated the R&B with the rock and roll, and from that emerged the boogaloo.

That’s where I came in, because as I said, to a lot of people, I’m not the greatest singer in the world. But I had to compete against guys like James Brown, Smokey Robinson. When the boogaloo came along, that was right down my alley because I could sing in English. I had studied all the classics and doo-wop and some show tunes so it was easy for me to make that transition and especially when I thought that it was a part of me. Doing the cha cha and singing in English, many people weren’t doing at that time and they called it the boogaloo.

But I found out that the beat was always around. Smokey Robinson was doing the same beat with Mary Wells songs, but people didn’t know what they called it. He didn’t call it the boogaloo and it was a cha cha because you can dance cha cha to some of Smokey’s music. I don’t think Smokey even knew what he was doing. I know he knew what he was doing when he composes, as he is one of the greatest composers ever. He was my idol. But what I’m saying is, having studied Smokey and a lot of guys, and what he and Sam Cooke did with chacha beats, fit in perfect for the boogaloo and me at that time.

What I’m credited for is that a lot of people weren’t singing the boogaloo the way I was. I use lyrics like Smokey and I told stories and my songs have lasted throughout the years.

SD!: How did you get started in music?

JB: Nineteen-Sixty-Five, after having a run in with the law. Joe Bataan was sent away. I did an indefinite period of five years in a reformatory where I was sent to straighten out my life. It was then I made up my mind. While I was away, I was going to pretend that I was in college and I was gonna read everything I get my hands on. I had the opportunity to study music under the tutelage of Mark Francis at West Coxsackie Reformatory.

Then I had made up my mind. My aspirations was to be a baseball player. I emulated and wanted to be Jackie Robinson all over. That didn’t transpire, so my second option was to get into music. Having no training. No background in music, except for what I did in the streets of New York, singing doo-wop with my hand cupped over my ear for harmony. I developed an ear for music, a sound.

Some people are born tone deaf, they can’t hear something. We didn’t have that problem we could orchestrate. We could harmonise. We could write, mentally, with our minds and our voices at an early age before we knew anything about music. And that’s the way I learned. I came home. I had several combinations of musicians that didn’t work out. Everybody quit on Joe Bataan. They couldn’t stand my aggressive tact.

SD!: How did you meet your first band?

JB: The first time I met these kids I was about 19 or 20 and they were the youngest band in Latin music ’cause they were like 12/13 year old kids and they were rehearsing in The William Edinger Auditorium and I walked in and I was appalled. Having been the neighbourhood tough guy. I said, what are you doing here? They didn’t say anything wrong because they knew my reputation.

Nevertheless, when I looked around, I got a brainstorm. I said, ”These kids are practising here and they don’t have a piano player.” So I initially took out a knife out of my pocket and I stuck it into the grand piano. I said, “I’m the leader of this band.”

Of course, that’s how we did things back then, I didn’t have any intention of hurting nobody, but just to have drama.

Nobody said anything and I said, “If you follow me and I become the leader of this group, I will take you to heights that you’ve never attained in your life.”

They didn’t know what the hell I was talking about. Neither did I. But nevertheless, by trial and error, they accepted me as the band leader. I was a strict militarian when it came to the music. Having had no background, I knew that I had to install discipline and we did this for six months.

My only problem was that they were underage, and their parents didn’t want them with Joe Bataan, not the neighbourhood tough guy, so I had to walk them home every night after rehearsal and convince their parents that I was a changed person and that I was no longer the old Bataan. But now all I wanted to do is play music. My aspirations and my goal was that it was going to take me 10 years.

The Cinderella story of the whole shebang is that it took us six months! In six months we were recording and had our first hit record as the youngest band in Latin music. Joe Bataan & The Latin Swingers.

SD!: How long did the band stay together?

JB: Well, they stayed with me for about three years. We were voted the band of the year. I mean, this was amazing when you think of all the greats that were playing at that time. Tito Puente, Machito. All these big-time names and yet we were voted the band of the year in 1968.

To get an award like that it had some significance, because these kids at that time were no older than 15 or 16 years of age. I was the oldest and to get that award, we were top shelf. I believe at that year we recorded the Riot album and we outsold everybody in New York four to one. I was given a gold record for that.

SD!: How did you get signed to Fania?

JB: I had tried everything. Some of the neighbourhood kids had got record deals and I didn’t know what to do, having not been trained. The kids were getting impatient after six months of rehearsing five days a week, three hours every day. They wanted to know, “What is the next step? When are we gonna get chance to be seen?”

I didn’t know, but by trial and error I started to look up the trade magazines and I started calling several people and people were getting wind of the band. We were starting to get popular even without a record and they invited me to go down to Roulette records.

Roulette Records at that time was controlled and run by Maurice Levy. I went up into the meeting and all these executives were there and they asked me, “Well what do you wanna do?”

I said “well, I’m having difficulty getting a deal in this industry because nobody wants to play my records unless I sign with them.”

He had a big cigar in his mouth and he said, “Well, that’s unheard of. Just let me take care of that.”

He called somebody on the phone. He cursed them out and said, “Okay, what else do you want next? They’re gonna play your records.”

I said, “Well I want to get paid.”

He said “We don’t pay anybody!“ (laughs)

You’ve got to understand I’m a young kid here. He’s a big guy standing at the big desk with everybody around him with a cigar in his mouth, if you saw the Frankie Lymon story, you would know what I’m talking about. Then somebody walks in the door. It was George Goldner from Cotique who started Roulette and he said, “Hey I got this kid signed to me!”

He said “What? What the hell am I doing here talking to this kid if you’ve got him signed.”

Then lo and behold, somebody else walked through the door. I forget who it was, he said, “What is he doing here? I got that kid sign too!”

Maurice Levy jumps up and says, “What are you a wise guy?”

I said “No, you got it wrong.” I said “I’m a youngster and I’m not that versed in the law and what is happening, but everybody here wanted me to sign the dotted line without reading it. My only defence was to sign contracts with everybody ’cause I know I’m underage and it’s not legal.”

They weren’t amused by that, and said, “Look we’re gonna teach you a lesson, right?”

He said, “Get out of here and we’ll think about when we’ll talk to you about recording.”

So they kicked me out into the street. I guess they had a big laugh about it and I walked with my head between my legs and I said, “Oh boy, now I blew it.”

You know there’s no chance for a job with them ever because these people control the industry. Then I got a call from disc jockey named Ricardo ‘Dick’ Sugar and he called me up.

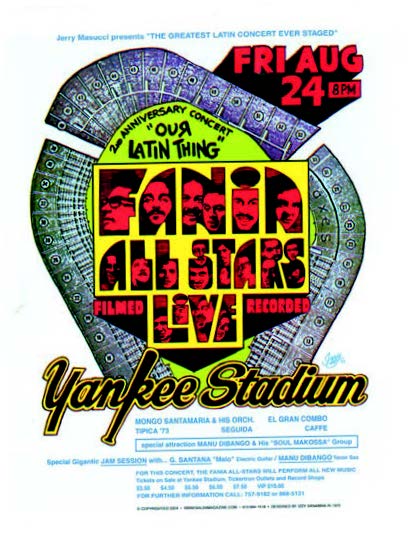

He said, “Joe, there’s a new guy that’s starting a label. An ex–cop lawyer and he wants to come and see you play. His name is Jerry Masucci and he’s starting a new label by the name of Fania.”

He came to see me at The Boricua Theatre and he said he liked the group and he wanted to sign me. I asked him questions and he was more nervous than I was when he was talking to me.

He said, “What do you want? I’ll record you!”

I said, “I want to get paid!”

He said, “Okay.”

I was shocked that he was gonna pay me. He said, “What else do you want?”

I said, “I wanna record right away.”

He said, “Okay, is next week too soon?”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing, that finally I was going to get a chance to go into the studio and the rest is history. I signed with Fania.

SD!: Tell us about your first recording experience.

I was in Veltone records. They were amazed that I had no charts. The kids all played by memory and everybody had to look at me while I played the piano. The strange thing about it is, Johnny Pacheco was the music director and he said, “Okay we’ll do one session today and we’ll do another one another day.”

I said “Look, I’m ready to do it now.”

He says, “Well how? We do everything by separation.”

I said, “No, put the whole band there. They’ll look at me and follow my directions and we’ll finish this.”

Well, the Cinderella story is that we finished that album in in five hours and ‘Gypsy Woman’ was born. He was so amazed that he had to call up Jerry Masucci. “I don’t understand, these kids finished the whole damn album. You gotta listen”and of course the rest was history.”

They picked ‘Gypsy Woman’ which was a Curtis Mayfield song. I forgot the lyrics when I was at the piano. I was so nervous that I sang the wrong words. I sang Curtis Mayfield words so he got half of the credit. I wrote the music. The next thing I know it was on the radio and we were the next Jackson Five in New York.

SD!: Tells us about your signature tune ‘Ordinary Guy’.

JB: ‘Ordinary Guy’ became a signature song because I must have recorded it seven times, in seven different versions. Fania was so in love with that song. They weren’t equipped to get me heard across the country. They weren’t equipped to go national, but nevertheless they tried. ‘Ordinary Guy’ just became a huge hit in New York and the tri-state area. It wasn’t until many years later when the Internet came out that people started to hear some of the material that I had done in the past and they have embraced it. There’s a lot of people who think some of the music is new, ’cause they’ve never heard it before.

SD!: Tell us about your approach to songwriting?

JB: I had this knack for writing. My training was the radio and listening to all the old groups of the past. You know The Ink Spots, The Solitaires, The 5 Keys, The Moonglows. Going on throughout history, I was very attached to lyrics. Lyrics came to me naturally after a while and then my imagination worked, hand in hand. I was able to compose songs in my own style, having limited musical ability. I had to find a technique that I could include my lyrics with the music and what my limitations were in playing the piano. It worked out for me.

I never knew what would happen if I had musical training. Maybe the heart and the essence of what I sang about would have never came out. Because I learned music backwards. That’s my trial and error and then I studied theory later, and then I found out two and two made four and I understand about the sequence of chords in music. I didn’t know an E flat from A minor but it all came to light after I started to study theory. As a result, it came into my style and how I wrote music. Things would fall out of the air for me when I was young. I guess it was because of all the experiences that I went through life. Having been incarcerated, having done extensive travels to Russia and behind The Iron Curtain and East Berlin, having been homeless in Las Vegas.

It’s all in my memoirs I’ve just written, a book called Streetology. It‘s something that you don’t learn in Cambridge or Oxford. You learn it in the streets of El Barrio. It’s a sixth sense that helps you to survive in this cutthroat world.

SD!: Tell us about the ‘Riot’ song, which is another example of your unique interpretation of other artists songs.

JB: Well, it was 1968. It was my third album. ‘Gypsy Woman’ was my first hit record, that was followed by ‘Subway Joe’. Some of my technique was always trying to bring something new to the table. When I was about to record the third album, I said “I wanna do something new.”

I was not satisfied what I had done prior and that’s been a style of my life, always to improve myself. I wanted to mix up the album but give it some kind of fire.

I heard this song on record by Smokey Robinson that said ‘Good Good Feeling’. I said, “Wow, that‘s a great song” and I attempted to learn the chords and then I said to myself, “He‘s never released this song.”

I was always good at picking songs that the public hadn’t had a chance to hear or didn’t know about. So I said, “I’m gonna change this song around and put it in a Latin vein.”

We got into the centre where we rehearsed and I started to play the song and everybody started to follow in. Finally, we had this great Latin beat that was going on. It was pulsating and everybody had smiles on their face. It’s something magic that happens when you create music, and everybody knew instantly that we had something that was unique because people started filtering in through the auditorium, sitting down to listen to us and people started to get up. The energy that was behind the song will never be duplicated in my life again.

We got into the centre where we rehearsed and I started to play the song and everybody started to follow in. Finally, we had this great Latin beat that was going on. It was pulsating and everybody had smiles on their face. It’s something magic that happens when you create music, and everybody knew instantly that we had something that was unique because people started filtering in through the auditorium, sitting down to listen to us and people started to get up. The energy that was behind the song will never be duplicated in my life again.

Once we put it together, I was determined that we weren’t going to just play this, but we had to perform it. At the time, the young kids, including me, had two left feet, but we made up routines. We danced to this song like you’ve never seen us dance. We changed the rhythm at the end to 6/8, which made it sort of like an African Montuno and the place went crazy, and then with the shouting, and everybody participating, it was a group thing. We know instantly we had something. When we performed that song nobody could stay still. Wherever we played, I’m not being arrogant, no band would follow us. After we completed that song, we had the audience join in. We did a conga line and I would take them out into the street! Never in my lifetime have I played a song for one hour straight and that’s what happened with the ‘Riot’. We changed the song name from a ‘Good Good Feeling’ to the ‘Riot’ because it was meant to be a riot of fun.

When I travelled to Berlin in 1973 and I went behind The Iron Curtain with these albums and I was stopped at Checkpoint Charlie and the Germans said, “What are you going to bring into our country? It looks like revolution.” I had to explain to him, ’cause they had seen the vinyl cover, that this is a song of joy and once I explained that, they let us through.

SD!: What were the biggest highlights looking back on your time at Fania?

JB: Getting a gold record for the ‘Riot’. The performances that I did at The Saint George Hotel performing that song or having a lot of the kids not only dance to my uptempo numbers, but to fall in love with a lot of my ballads. I think that’s the one advantage that I had over all the other bands.

Most of the Latin bands that played during that era had to attach a singer to the leader so that they could vocalise. But Joe Bataan was the bandleader and the singer, so my name is synonymous for what I’ve done. Other bandleaders, just like other groups that break up, have to retain their name. What they find out is that they are incorporated with more than one person. There’s always seems to be some difficulty in who would take the rights to the name. Joe Bataan has never had that problem, and I thank God that I never named the group anything else but Joe Bataan. Because I’ve been able to work all these years!

SD!: Tell us about the circumstances that led to toy leaving Fania.

JB: It was inevitable. Yeah, it was supposed to happen. Everything was destined. After that I found spiritually that God had his hand on me and he wanted me to do other things. It was a blessing when I left Fania because I went international. I started Salsoul records and I was called to perform in Europe and I’ve never stopped. I was able to travel all over the world from Australia to Shanghai to Japan, The Philippines to South America and Ecuador. I’ve been all over on this journey. I would have never been able to do that if I would have still been with Fania. I became independent by handling my own business for years. That’s what has endured me to my public. I’m still the same guy. Known by ‘Ordinary Guy’ and I’m the first one on stage and the last one to leave.

Order the issue with this article here