The Beach Boys and ecololgy– Counter-Cultural musings from TSPTR. Dossier #4

In the fourth of our monthly counter-cultural musings from TSPTR, we look at the ecological themes of THE BEACH BOYS to tie in with this month’s issue’s Dennis cover

The rise of the American counterculture between the early ’60s and mid-70s was closely associated with the growth of environmentalism. Popular music during this period identifies and mirrors these patterns of change and continuity in the articulation of its countercultural, ecological and related sensibilities. It was during this time that The Beach Boys leader Brian Wilson and lyricist Van Dyke Parks collaborated on a collection of songs embodying such a degree of progressive thinking that the music industry outright rejected it, causing the group to flounder. Then, one single event brought environmental concerns more into focus than any other; an oil spill in the Santa Barbara Channel in 1969, killed more than 10,000 sea creatures and devastated the coastline. What followed was a wave of campus activism that led to the first Earth Day, in ’70, bringing the movement to the mainstream. Millions of Americans now became aware of environmental concerns and what had formerly been considered commercially high-risk in the music industry had by ’70 become good business as once marginal environmentalism gained broader acceptability. Thus did “America’s band” articulate the flowering, greening and fading of the counterculture.

The Beach Boys are not usually associated with ecology. On the contrary, their early image is synonymous with a consumerism as environmentally heedless as it is hedonistic. The Beach Boys are not readily associated with the American counterculture either. The style of early hits meant that by the time the underground was reaching its cultural and social zenith they were being perceived as obsolete by a significant number of alternative movers and shakers. Writing in the new “hippie bible” Rolling Stone in December ’67, editor Jann Wenner dismissed the group as disappointing live and their music as shallow. Though they had been invited to play at the seminal Monterey Pop Festivalin June ’67, they did not appear, bolstering a wider sense among the burgeoning counterculture that The Beach Boys time had now passed. Their music was catchy but disposable; they came from plastic land, LA, not hippie central San Francisco. Jimi Hendrix summed up such opinions of the band in a line from a song on his debut album Are you Experienced? that same year: “To you I wish to put an end / and you’ll never hear surf music again”.

Hendrix, as it happens, overstated the case. Fashionable dismissals notwithstanding, away from the pop charts The Beach Boys began exploring the new aesthetics more in tune with countercultural concerns, particularly the environment. Not all at once and not without internal conflict, by the early ’70s the band would have covered many overlapping bases – from romantic primitivist to pastoral and mystical, from conservationist to deep ecological – in what was a growing preoccupation with the natural world.

The Beach Boys engagements with environmentalism and counterculture were informed by and threw light on a broader pattern in the relationship between the American music industry and some of its social and cultural contexts. During the mid-60s one faction within and around the group articulated environmentalist faith in the ascendant amongst a growing and influential minority of their fans and broader audience. Dennis Wilson particularly had become less confident or interested in the authority, knowledge and objectives of their major record label or the preferences of their mass market. Only toward the end of the decade, as green issues began to gain a broader and more sympathetic hearing among audiences, were the perceived risks deemed sufficiently acceptable and the potential benefits sufficiently vital to prompt the group as a whole to express more explicitly an ecological commitment.

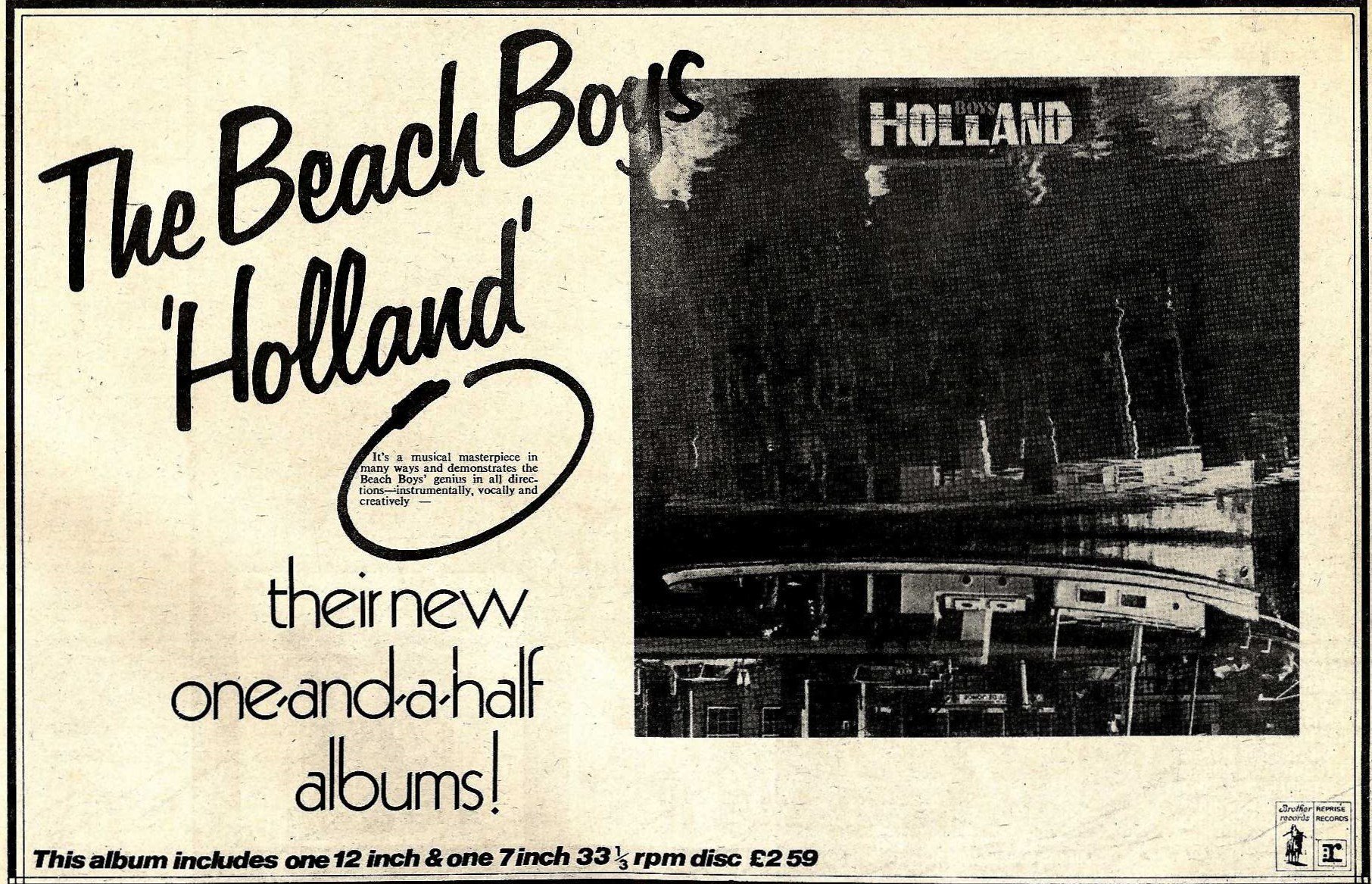

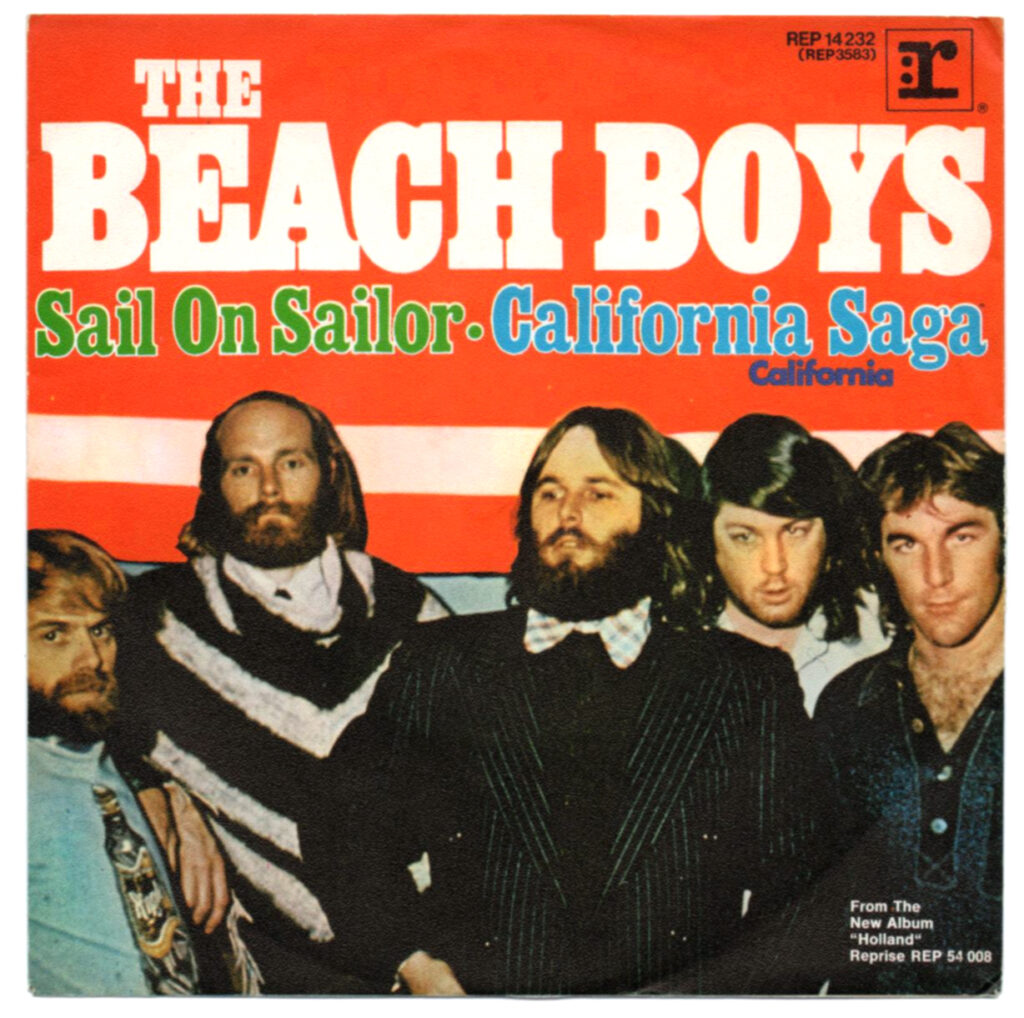

By this time Brian Wilson was himself coming to embody, involuntarily, some of the costs of countercultural excess and consumerist self-indulgence, a combination leaving him as damaged and endangered as the environment whose fragility he had begun to highlight. Brian Wilson and Van Dyke Park’s innovations on Smile would ultimately enjoy widespread recognition as an artwork that was as socially and culturally prescient as it was musically and lyrically inventive. The Beach Boys, for the most part in their original leaders’ absence, would go on to establish the celebration of the natural world as a part of their band ethos, much as environmental concerns have become omnipresent within the broader American public platform. The group would come to serve as an implausible yet illuminating index of commercial pop culture dealings with both ecology and the counterculture, as their differing tides ebbed and flowed. Nineteen-Seventy’s Sunflower featured the natural world in its own right, not taken for granted or serving exclusively as romantic context or metaphor but moreover as a psychedelic symbol or spiritual analogue. While Surf’s Up (’71) contains a number of biocentric cautionary tales about the human condition and the potential for this to envelop the natural world. With ’73’s Holland, The Beach Boys arguably reached their song writing zenith on this fascinating, periodically transcendent album. It’s centrepiece being a homesick, heartfelt exaltation titled “California Saga”, reaffirming their early ’60s West Coast mythology.

With the counterculture beginning to wane and environmentalism becoming more mainstream, The Beach Boys would release their most commercially successful album ever, ’74’s Endless Summer, a greatest hits compilation highlighting their original blend of cars, surf and romance with a scarcely a trace of an ecological reference. By late ’74, the record label was hungry for a new Beach Boys record thanks to their recent success, but old frictions had once again started to develop within the band. With Dennis Wilson and Blondie Chaplin wanting to go further down the more explorational and ecological Holland route, and Mike Love and Al Jardine wanting to incorporate a “retro” sound channelling their earlier hits (a la Endless Summer), they were at loggerheads. At the 11th hour, Dennis and Jack Rieley took over production duties from a suffering Carl Wilson and forged ahead with a new album they tentatively titled Ecology. Containing tracks that would become the stuff of legend among Beach Boys afficionados, the album would never be released. A mentally unstable Brian Wilson was coerced back into the studio by Mike Love’s faction and the result was ’76’s woeful (semi) covers album 15 Big Ones. Only Dennis Wilson would pursue ongoing environmental themes, his critically acclaimed ’77 solo album Pacific Ocean Blue, writ large as a beautiful, multi-layered paean to humanity and the natural world.

The Beach Boys would continue a widely popular, highly profitable, nostalgia-oriented career for years to come. As a band their engagements with environmentalism and the counterculture were at first non-existent, then expansive, thereafter strategic and selective. They may be read as emblematic of the ways in which the highly market sensitive American popular music industry came to terms with social and cultural movements whose motives were not primarily economic. As the folds and tears in its musical and personal fabric demonstrated, the group was positioned across a network of commercial, social and cultural fault lines that were particularly stressed during these years. Though damaged by the experiences, The Beach Boys leader Brian Wilson would ultimately make enough of a recovery to complete his work with Van Dyke Parks almost forty years after its abandonment.

Order issue #118 with Dennis Wilson on the cover, and a fab feature by Martin Ruddock here

the beach boys from 68 to 73 were at their peak. sadly it was gone due to the oldies being more in the set and carl and dennis reduced to sidemen for the mike love show. for me its 67 to 73. RIP carl and dennis.