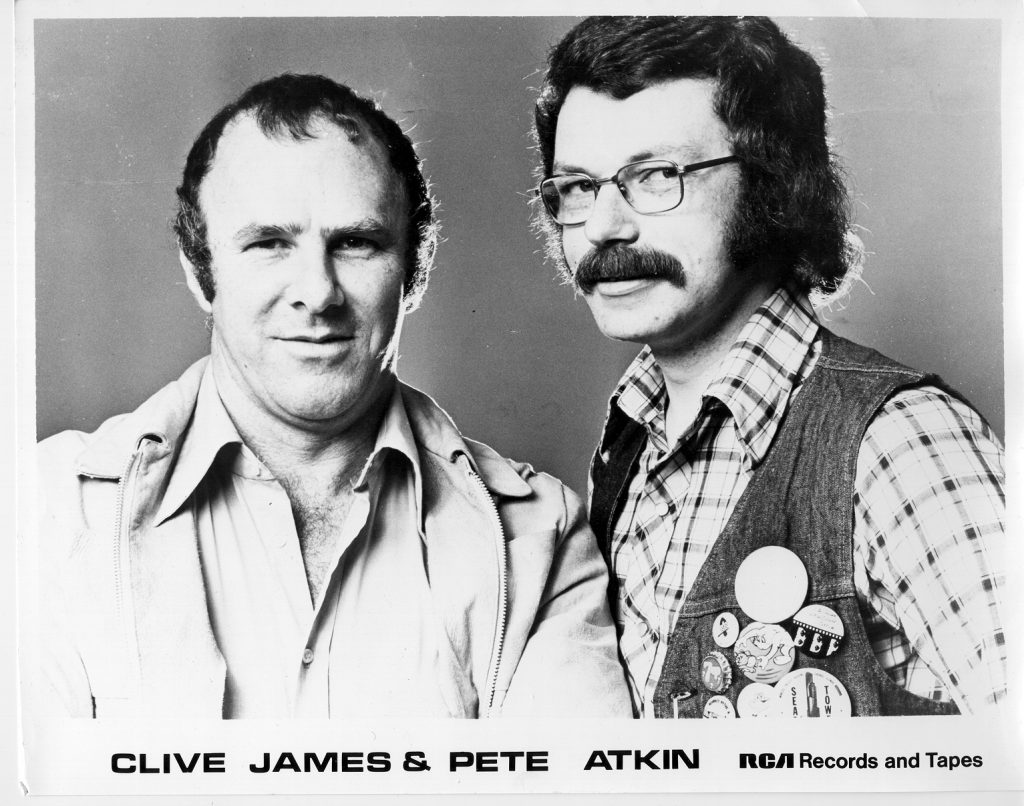

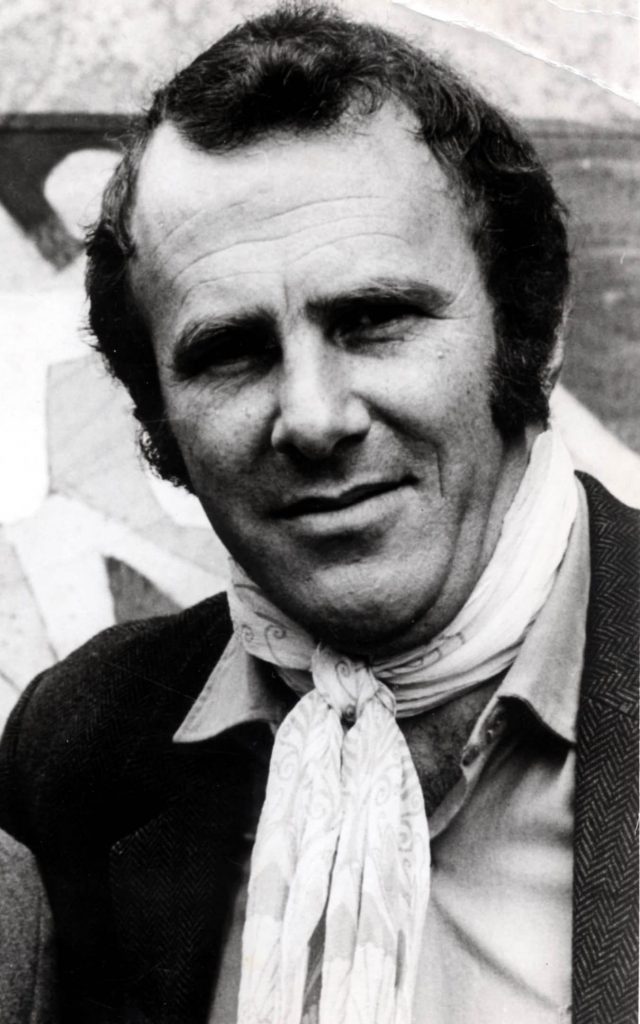

RIP Clive James… musical partner Pete Atkin remembers

Shindig!: In the early ’70s you were never really uncool. You wore borderline hippy attire with lots of denim, wacky jumpers, stack heels and had a gypsyish demeanour… at least judging from the photographs. Led Zep etc may have had long hair and looked wild, but your “geography teacher” look probably did not muster for “cool” with the teenagers back then. And I guess that really was not something you were aiming for. However at the tail end of the last century with Jarvis Cocker types giving the ’70s style a new found fashion your dress/appearance attitude now looks very cool.

Pete Atkin: I think I always felt I was uncool, or at least I never felt that I was actually cool – a subtle but important distinction, if such distinctions can ever be said to be important. In practice “trendy” or “untrendy” is probably the distinction we would have made at the time, although I guess that’s not really the same thing. Maybe the difference is that “trendiness” is something you can aspire to, while “cool” is something you either have or don’t. You can certainly be both trendy’ and “uncool”, as many surviving photos of people from the late ’60s and early ’70s bear witness.

Either way, if I was ever going to be thought of as “cool” it was going to have to be via a route other than fashion. As one of the ones who was not naturally sporty at school, I used to hope to ingratiate myself with my peers and avoid being beaten up by the sporty ones by a reputation for “mucking about” and with pop music. (“Pop music” in the early ’60s was an all-embracing term that had not yet separated off from rock ’n’ roll and all the sub-categories which now have their own distinct definitions).

Even by the time I started recording in 1970 I never felt completely comfortable with the world of fashionable image. I’m sure I wished I was trendy, but I had no idea of how to do anything about it. Don Paul, my producer at Essex Music, made some attempts to trendy me up when they got a release deal for my first recordings. He sent me to a smart hairdressers’ in Beauchamp Place near Harrods who wanted to give me an afro (now there would have been some good pics). I persuaded them not to, but since I didn’t have any idea at all of what I did want him to do, I ended up with a haircut pretty much exactly the same as I could have got from my usual local joint for a tenth of the pre-decimal price.

It was Don, too, who lent me the velvet suit for the cover shoot for that first album, Beware Of The Beautiful Stranger – the one with me leaning against the tree with the gypsy caravan in the background and the out-of-focus girl sitting on its step (it’s her hairdresser who was credited on the sleeve, by the way, not mine). It was a Mr. Fish suit, which apparently was pretty damn smart. Don tells me he still has it. It would be fun to think its history might make a fortune for him on Ebay, but I don’t think he’s holding his breath on that.

So, no, I wasn’t really aiming at anything at all in the way of an image, I’m afraid. I certainly wasn’t trying to look like my old geography teacher, which would have been even more bizarre and have consigned me to the uncool bin for ever. Any resemblance to anyone else’s geography teacher is entirely unintentional.

SD!: The big question. How did you perceive yourself in 1971? Which musicians did you feel a kinship with, who did you aspire to be like? Was your music beyond fashion? Did you want to be contemporary? I guess, this also has something to do with attire.

PA: Image unquestionably mattered in ’70, but it didn’t seem to matter quite so much as it does now. I think I’d managed to convince myself that if the music was successful, then the image thing wouldn’t matter much at all. Such an attitude these days would seem almost laughably irresponsible. Of course, it’s always possible that I’m simply raising something I couldn’t help about myself into a principle which I then congratulate myself on practising.

What I wanted, I suppose, was enough success to allow me to go on making music for a living. And at the start back then that meant writing. I had always enjoyed performing (the years have proved that the show-off gene is dominant and persistent) but the ambition originally was that Clive and I would make a living from writing songs. That’s why I started out by approaching publishers rather than record companies. And that’s how it came to be that it was a publisher (Essex Music) who funded the demos that ended up being released commercially as Beware Of The Beautiful Stranger.

Musically, I always assumed (naively, I now realise) that the more original my stuff was, the more likely its success. And more than that, I thought that it would always be a mistake to set out deliberately to imitate the people I admired most. I’d be sure to be caught out. So if I came up with an idea that sounded to me a bit like something else, I’d always change it to avoid the accusation of having nicked it. In practice, of course, there’s no way I could ever have sounded like Elvis or the Band or The Mamas & The Papas or Buddy Holly or The Beach Boys or any of the great Motown artists, so I was probably once again trying to make a virtue out of the inevitable, and making myself sound just too different for big commercial success.

It’s possible, I suppose, that if I had indeed tried to make my songs and the recordings more self-consciously contemporary – trendy at the time – then they might sound more dated now than they perhaps do. I don’t know. That’s not really for me to say.

But anyway, no, I wasn’t trying to write or to perform in any particular style. Clive and I have often said that we always wanted to try to incorporate ideas from the whole range of 20th Century popular songs into our stuff – still do, in fact – including most especially the great Tin Pan Alley songwriters: Rodgers & Hart, Cole Porter, the Gershwins, Irving Berlin, Noel Coward, Johnny Mercer – the list goes on. If we have ended up with any distinctiveness, maybe that element is what provides at least a part of it.

SD!: Having moved to London where did you hang out? Did you embrace a “rock ‘n’ roll style lifestyle”? Where did you go (clubs etc)? What current bands did you enjoy, whether as inspiration or just as entertainment?

That’s easy: the pub. That was as far as “hanging out” went. The “scene” (whatever that was) was always far away. Whenever I happened to find myself in the context of any manifestation of the “scene”, I would quickly be wishing I was somewhere else, and put my best efforts into removing myself to that somewhere else as soon as possible. So no, I was about as un-rock-and-roll as you could get.

SD!: The live feel of the recording and production is sheer class… the session players are excellent and there is a groove throughout. I can hear similarities to Nick Drake and American artists like Love and Tim Buckley… was this something you were aiming for?

PA: Nick Drake I knew about, mainly thanks to my younger brother, but I was never into him as deeply as he was. Love and Tim Buckley I was scarcely aware of at all, I’m afraid. The very early Joni Mitchell impressed us, but there were several good reasons why she didn’t constitute a role model for either of us.

However, I’m sure there is always a kind of stylistic osmosis in any era, something that somehow permeates everything that everyone’s doing at a given time. I suppose that’s how it’s possible to tell from the playing roughly when any recording was made.

The “liveness” of the recording of my ’70s albums was partly preference on my part, but mainly practicality – financial practicality. There simply wasn’t the budget for the kind of studio time which might allow me to try to build up a complex created sound in the way the Beatles had pioneered. I might have enjoyed that, but apart from a bit of judicious over-dubbing now and then, it was a non-starter. And besides, I did like the ‘live’ feel – still do..

On Driving Through Mythical America it really was live, though. Those tracks with brass on were recorded absolutely live, as you hear them, rhythm, brass, vocals and all. What you hear is what happened. It’s not really ideal from a sound balancing point of view but, as I say, it was a matter of budgets.

SD!: What are your favourite songs on the LP and why!

PA: I never listen to my own stuff for pleasure – does anyone? – so there are long gaps between listenings for me, and that means that when I do I’m usually surprised by something or other, something I’d forgotten about, often a tiny detail, small nuggets of pleasure amongst the cringing embarrassment of wishing I’d done things differently, done that vocal one more time, relaxed on that tempo a bit more, taken that key down a couple of semitones, added a bit of this or that, taken a bit of this or that away.

But since I was keen to include all of these songs on the album – and we always had far more songs on the possibles pile than we could fit in – I suppose they are all favourites in a way. There are some of them I’ve continued to perform many times over the years since, so they’ve kind of carried on with a life of their own, and with hindsight I perhaps feel most fondly towards some of the ones I’ve performed much less often, and some of the ones which have attracted less attention generally. ‘ The Pearl-Driller’, maybe, or ‘Lady Of A Day’. But that’s not because I think they’re somehow better than the others. Nanci Griffith once said that every album has at least one song on it which ends up never being requested, and that that song ends up being her favourite.

SD!: Why do you think Driving Through Mythical America gets the most attention now from your ’70s albums?

PA:, I don’t know – does it? It’s the one which overall sold the least well of all the albums in the ’70s. It encompasses a very wide range of styles and approaches, so I’m specially glad to know you think it hangs together stylistically. At the time I think I worried that it didn’t. It may be down to the particular songs. Again, that’s probably not for me to say – not because I don’t want to, just because I don’t know how.

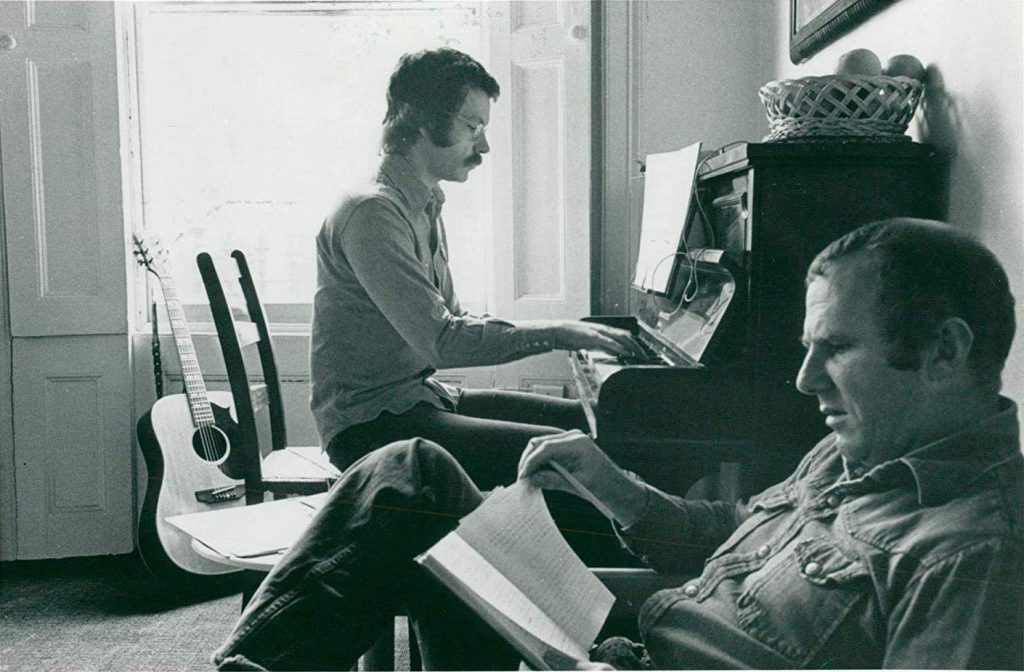

SD!: How integral was Clive beyond lyricist? Did he lend you records: rock, jazz or otherwise that helped form the music?

PA: Well, for a start, Clive’s influence on me simply as lyricist went beyond straightforwardly providing the words. Lyrics as original and effective as his were bound to have an effect in themselves on the music I was writing, if only because the ideas they were trying to communicate were often not the usual kind of thing. He was familiar of course with the classic Tin Pan Alley songs and with ’60s stuff, but generally it was more likely that I’d be introducing him to interesting new stuff than the other way around.

SD!: Did the wonderful musicians (Chris Spedding etc) have strict rules to follow or were they free to let rip when needed?

PA: I’m afraid I don’t think I ever gave them the opportunity exactly to “let rip”, but the real answer to that is somewhere down the middle. The time constraints in the studio meant that it just wasn’t possible to spend time teaching the songs to the musicians. It wasn’t necessary anyway, because they were all such great musicians, and all so good at sightreading, that having provided them with a reasonably detailed written-out part, once I’d set the tempo they’d just be able to play it pretty much straight off – that includes the drummers, of course. Some of the finished tracks are literally just the second or even the first time they’d played the whole song through. So I’d always let them know that the written part wasn’t necessarily meant to be stuck to rigidly, it was more a substitute for having to teach them the song, a way of quickly giving them an idea of the kind of thing I wanted them to play.

The Masters Of The Revels

Shindig! salutes the unique songwriting skills of Pete Atkin and Clive James with 11 selections from Pete’s own half century of albums and a few choice interpretations by colleagues and admirers.

‘Girl On The Train’ – Pete Atkin

(from Beware Of The Beautiful Stranger, Fontana, 1970)

‘Thief In The Night’ – Pete Atkin

(from Driving Through Mythical America, Philips, 1971)

‘Tonight Your Love Is Over’ – Julie Covington

(single A-side, Columbia, 1970 – Pete’s version appears on Beware Of The Beautiful Stranger)

‘Carnations On The Roof’ – Pete Atkin

(from A King At Nightfall, RCA, 1973)

‘An Array Of Passionate Lovers’ – Pete Atkin

(from The Road Of Silk, RCA, 1974)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZpRf7siuph4

‘The Flowers And The Win’e – Doug Ashdown

(from Winter In America, Philips, 1974)

‘Sessionman’s Blues’ – Pete Atkin

(from Secret Drinker, RCA, 1974)

‘Errant Knight’ – Pete Atkin

(from Live Libel, RCA, 1975)

‘Touch Has A Memory’ – Wizz Jones

(from The Grapes Of Life, Run River, 1987)

‘Senior Citizens’ – Pete Atkin

(from Midnight Voices, Hillside Music, 2007 – original version on The Road Of Silk)

‘The Beautiful Changes’ – Pete Atkin

(from The Colours Of The Night, Hillside Music, 2015 – original version by Julie Covington on The Beautiful Changes)

Dear Jon & Andy, I’m really glad that Shindig introduced me to Pete Atkin’s and Clive James’ music ten years ago. I love the first two albums very much. So many great tunes incl. beautiful arrangements. It’s truly sad that Clive James has died. RIP. Farewell Clive. D.P.