A Change of Scenery: Another playlist

Revered stars and cult heroes, seeking the challenge of a new recording environment or relocating for good. L’Édition Spéciale de Shindig! has brought us to France, and that’s where our quest for visionary travellers begins. Paris, then the world: we find Marianne, Dusty and the others, packing for Montparnasse, Memphis or hidden havens. Just remember to make it as much about the journey as the destination, and let the revelations sing. CAMILLA AISA serves up the menu

Marianne Faithfull

‘Paris Bells’

Travels can turn into new lives, and the love between a happy expatriate and their adoptive home can be openly reciprocated. In 2011 Marianne Faithfull was made Commander of Arts and Letters by the French government. She then recalled starting to visit Paris in 1964 – “That is when I remember first falling in love with Paris and I have loved it ever since.” In fact, her self-titled release of 1965 already showed signs of indelible attraction (in the form of ‘Paris Bells’, a smitten postcard-pretty homage that would eventually turn into more significant commitment). Some 50 years later Marianne writes songs from her Montaparnasse home. As the final notes of her latest album – last year’s Negative Capability – play, times of reflection, heartache and loss face the muse of a lifetime: “I’ve seen the moon in Morocco and I’ve seen the moon in Brazil. Oh, I’ve seen it in the darkest times coming over the hill. In Martinique it shines on the sea, but in Paris it usually shines on me”.

Dusty Springfield

‘What Do You Do When Love Dies’

Forget how great Dusty In Memphis, now a certified classic, sounds. Back in 1968, the pairing of Dusty Springfield with Chips Moman’s American rhythm section seemed improbable, challenging to say the least – as the Shindig!#88 cover story has revealed. In the words of Jerry Wexler, one third of the album’s eminent production team: “How can you put Dusty Springfield in with this band of redneck ragamuffins with that Southern style?” It took some time and some laborious recording sessions. As Dusty later explained, “I was someone who had come from thundering drums and Phil Spector, and I didn’t understand sparseness. I wanted to fill every space. I didn’t understand that the sparseness gave it an atmosphere. When I got free of that I finally liked it, but it took me a long time. I wouldn’t play it for a year”. Of all the Memphis recordings, ’What Do You Do When Love Dies’ is the one track that didn’t make it on the LP; it still glows with the kind of powerful sparseness Dusty grew to appreciate, and we keep adoring more and more.

Fleetwood Mac

‘Come a Little Bit Closer’

That a group of struggling heroes of the revered British Blues went crazy and West Coast all of a sudden at the hands of a young American couple is an oblivious over simplification that could only work for a Hollywood blockbuster of the Bohemian Rhapsody sloppy persuasion – or, of course, for people who like to type that “There is only one rue Fleetwood Mac” in endless Facebook bellicose threads at every possible opportunity. But truth tends to be more complex than oversimplifications, and oh do Fleetwood Mac love complex. Bob Welch led his bandmates to the American West Coast, and took the helm of the so-called “bridge” era, a period of Fleetwood Mac history that so deserves to be rediscovered and properly valued. Heroes Are Hard to Find, the last Welch-fronted album the band released,has all the harmony-filled tension that would burst and triumph one year later in the dawn of the Nicks-Buckingham era. And ‘Come a Little Bit Closer’ might very well be one of the most gorgeous songs Christine McVie has ever written.

Jackson C. Frank

‘You Never Wanted Me’

When Jackson C. Frank came to England in 1965, he wasn’t exactly answering some sort of artistic call. Actually, he was looking for cool cars. Esquirehad recently proclaimed London the place to be for fashionable automotive shopping, and so he quickly caughta boat to England. Fortunately enough, he brought a guitar with him on the Queen Elizabeth: while on board, he started writing songs, and Blues Run the Game was one of those. He landed in folk-obsessed Soho, and turned the tables forever. “Jackson is one of the great songwriters who pointed the way for all would-be singer-songwriters”, Bert Jansch commented decades later. “He was a good example to follow because he wrote about how he felt about life and that made it easier for the rest of us to write songs”. His self-titled debut LP was released in ’65, produced by then roommate Paul Simon. According to Jansch, “when his album came out, everybody took note. For a time, he had as much influence on the English folk scene as Bob Dylan”. Taking note better than anybody else was Sandy Denny, who would later state her very first songwriting influences had come from him. ‘You Never Wanted Me’was one of her favourite Jackson songs, and one of the great gems she helped saving from ill-fated obscurity.

Neil Young

‘Bad Fog Of Loneliness’

Three years after Dylan’s Nashville Skyline had paved the way for the fruitful affiliation of country and counterculture, Harvest reasserted what a compelling intersection that was – even though not everybody seemed to appreciate it at the time. Neil Young turned up in Nashville when he was invited to The Johnny Cash Show alongside Linda Ronstadt, James Taylor and Tony Joe White. Little did he know that while in town he would find a new producer and a new band. During his first session in the Music City with Elliot Mazer and The Stray Gators, Neil recorded two future classics, ‘Heart Of Gold’ and ‘Old Man’ plus ‘Bad Fog of Loneliness’, a song that was initially intended to be played on The Johnny Cash Show. It didn’t make it on the record, but it was later included in live albums and boxsets. It’s the Harvest sound at its best: Ben Keith’s sweet pedal steel, ‘Needle and the Damage Done’-like melancholy, and mates Linda and James on backing vocals duties.

William Tyler

‘Fail Safe’

Born in Nashville, William Tyler recently relocated to California – and as the title suggests, his latest album Goes West makes a point of reflecting his new environment. “L doesn’t feel like home,” he recently told Shindig! “But the whole reason I moved out there was to get away from home. It’s astunningly diverse miasma of culture and geography and displaced creative souls, so I guess I truly hope it continues to shape me!” It’s all there, what we so untiringly love about guitars in the West; it’s evocatively intertwined with Tyler’s unique style, and ‘Fail Safe’ is a perfect example of how winning this combination is.

Vashti Bunyan

‘Jog Along Bess’

Quaint travels and a company of four: Vashti Bunyan, Robert Lewis, dog Blue and horse Bess. Destination: Donovan’s Scottish islands, a haven and heaven for poets, musicians, wanderers of all kinds. The plan: stopping by villages to sing songs and share dreams. The setting: latent Arcadia waiting to be rediscovered. Well, yes, it turned out to be more difficult and less dreamy than expected. They left in the Summer of ’68 and arrived in Skye more than a year later. But at least the bumps in the road and the less picturesque itineraries proved to be musically fruitful: “I think the most jiggedy-joggedy songs were written in the worst bits of industrial England” Vashti later recalled, “where it was really horrible to be going through. Like the outskirts of Manchester, where there were a whole lot of children in the street without shoes.”

Led Zeppelin

‘That’s The Way’

Among many things, ’That’s the Way’ deserves credit for surprising Lester Bangs. Yes, a Page-Plant song from 1970 actually overwhelmed the Lester Bangs. “It’s the first song they’ve ever done that has truly moved me” he wrote. “Son of a gun, it’s beautiful.” The song was written in the Bron-Yr-Aur cottage, the peaceful Welsh retreat that would significantly remodel the duo’s approach to songwriting. It’s thanks to those serene surroundings that Led Zeppelin picked up what Bangs most liked about the song: the power of restraint.

The Lollipop Shoppe

‘Underground Railroad’

Sometimes a stop along the way can turn into the destination of a lifetime. For Las Vegas, Nevada band The Weeds that stop was Portland, Oregon. Not only did they end up releasing what is probably the most fascinating psychedelic LP to come out of the PacificNorthwest (1967’s Just Colour, after changing their name to The Lollipop Shoppe), but they also gave the Northwest underground one of its most emblematic music heroes. Frontman Fred Cole would later form, among many other groups, legendary DIY band Dead Moon. Even when The Lollipop Shoppe were a bunch of new comers, songs like ‘Underground Railroad’ immediately managed to blend the garage fervour, cathartic dark psychedelia and proto-punk urgency that would make Northwest music stand out for decades to come. It was ’67, and Fred Cole chose Portland. Or, perhaps, Portland chose him.

Wooden Shjips

‘These Shadows’

Some 45 years after The Lollipop Shoppe, hypnotic Bay Area quartet Wooden Shjips also moved to Portland. Right before the relocation, 2011 LP West proudly showed the Golden Gate Bridgeon the cover; two years later, the new Northwest influence revealed itself through the sound of Back To Land, especially on the cloudy trippiness of standout track ‘These Shadows’.

Jess Williamson

‘I See The White’

The Summer Of Love might be long gone, but the Californian call seems to be still in full force. There’s no shortage of young artists going west – sometimes chasing ineffective fantasies. But sometimes we get to discover a beautiful gem of a record, and fall in love with the idea of musicians moving to California all over again. This is the case for Jess Williamson, who moved to L from her home state of Texas in 2016. The West Coast knows how to make its sonic mark on albums, and that surely worked on the trippy Americana of Cosmic Wink, one of the most intriguing releases of last year. But fine influences can be textual, too: “Tell me everything you know about consciousness” Jess Williamson sings on standout track ‘I See The White’, and it’s an invitation that could come right out of those mythic ’60s.

Caetano Veloso

‘London London’

At the beginning of 1969 Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were arrested for the “degenerate” nature of their politicised music. The military wanted them out of Brasil. So they managed to organise a concert that would allow them to found the forced transfer, and sent their manager to Europe on a reconnoisance mission. Where to go? ”Lisbon and Madrid were out of the question as Portugal and Spain were under a heavy dictatorship. Paris had a boring musical ambience. London was the best place for a musician to be,” Gil asserted. And while he embraced London immediately, Veloso had to deal with homesickness. His 1971 self-titled LP, recorded in England, reflects this wistful condition – ‘London London’ painting a candid picture of his new life in exile. In the midst of melancholy, being close to the rock music he had always admired was fruitfully inspirational. “I learned about authenticity,” he said decades later. “I was initially reluctant to play guitar on my own records, and would delegate that to more skilled musicians. But producers convinced me that the frailties of my guitar style were part of the charm of the song. That was very liberating”.

Paul Horn

‘Mumtaz Mahal’

In the second half of the ’60s pretty much every musician wanted to go to India. A few lucky pop stars managed to actually go – most famously, The Beatles. Among the colourful gang that kept them company while visiting the Maharishi was fellow Transcendental Meditation practitioner Paul Horn. Yes, in the second half of the ’60s virtually every musician managed to incorporate Indian flavours into their music. But not every musician went on to record it inside the Taj Mahal – as Horn did in April 1968. Can you imagine that? “Sorry Beatles, I won’t be back for dinner tonight – I’ve got something quite historic to do.”

Wings

‘Picasso’s Last Words (Drink To Me)’

Double travel for this Wings classic: first, to Jamaica, where none other than Dustin Hoffman challenged Paul McCartney to write a song about whatever popped out of the first magazine at hand, on the spot. It was 1973, and Pablo Picasso had just died. The article they found reported the artist’s last words, and so did Paul: “Drink to me, drink to my health. You know I can’t drink any more.” Yes, Dustin, Paul could indeed write about anything. And then it was Nigeria: Lagos, where Wings recorded their acclaimed Band On The Run LP following Paul’s longing for exotic atmosphere. Ginger Baker was also in Nigeria at the time, and invited them over at his ARC Studio. Paul brought ‘Picasso’s Last Words’ with him and recorded it there with Linda and Danny Laine. Meanwhile, faced with an arduous question – what do you play when you’re recording with a Beatle? –, Ginger Baker found a most ingenious answer. Well, of course: a tin can full of stones.

Kendra Smith

‘Space: Unadorned’

Moving can sometimes have more to do with disappearing than relocating. And when it comes to dropping out of sight it is likely that nobody can sing about it better than Kendra Smith. After wishing the world sweet happy nightmares with Opal, the former Dream Syndicate bassist moved to Northern California, to the woods, in the early ’90s. In 1995 she released the aptly titled album Five Ways Of Disappearing, a collection of dreamy acid-folk cogitations reflecting an existence off the grid: Eastern sounds questioning the cosmos, a pump organ among redwoods. The press release for the record quoted Kendra describing her new “primitive” life as “physically and ‘psychically” demanding. But it’s satisfying to me. There are many opportunities to study nature and conduct scientific experiments. I know enough of humans already”.

Nektar

‘It’s All In The Mind’

The late ]60s and early ’70s found quite a handful of Englishmen making music in Germany. Members of Nektar started playing together in 1969 in Hamburg and released their first LP, Journey To The Centre Of The Eye, two years later. It was a spacey concept album that blurred the lines between ambitious psychedelia and the dense progressive that was starting to emerge. “My mind expands to a great degree,” they sing on the epic ‘It’s All In The Mind’, where the album’s protagonist, an astronaut facing a new galaxy, deals with devastating consciousness: it’s all so overwhelming, as Nektar’s phantasmagoric guitars underline, that he doesn’t want to see anymore. As the next song arrives, he renounces his eyes and starts to only see with the mind.

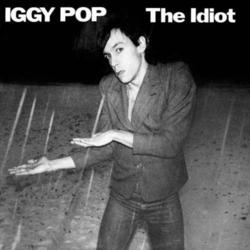

Iggy Pop

‘Nightclubbing’

When it comes to musicians travelling to Germany in search of new inspiration, two names pop in all our minds: David Bowie and Iggy Pop, the English duke and the runaway Stooge. They were famously looking for retreat: from addiction, and from their own fame. But something else was drawing them to Berlin; Iggy Pop later recalled: “I’d always been fascinated with the Germans – a lot of guys in rock ’n’ roll liked the uniform, you know. I went there with Bowie and we basically dug the whole idea that this was Berlin… this was a war zone, a no man’s land” ‘Nightclubbing’, written with Bowie, is the sound of their decadent days in no man’s land – “oh, isn’t it wild?”.

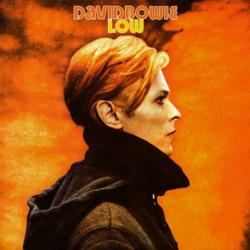

David Bowie

‘Speed of Life’

For Bowie, an appealing aspect of Berlin was the anonymity it granted him. You can picture him observing life – the life of ’70s Berlin, present futurisms in the making –, observing the German music scene, undisturbed. The impression so vivid it didn’t require any words: and so Low opens with Bowie’s first instrumental, ‘Speed Of Life’, a living metallic cityscape conjured with Brian Eno.

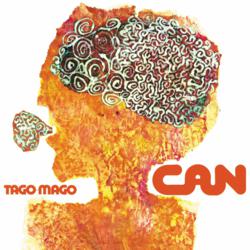

CAN

‘Oh Yeah’

Since we’re already in German territory, it’s worth paying a visit to everybody’s favourite German band – a group of wild experimenters who didn’t have to travel far to find the right environment for their seismic early records. CAN traveled to the countryside near Cologne, and moved in the Schloss Nörvenich castle with their equipment. The castle would eventually turn into a sort of additional instrument: “It had a huge entrance hall which actually was our reverb,” Irmin Schmidt recalled. “It had an exceptional, beautiful reverb, so we were always putting loudspeakers into the hallway and using it as a reverb chamber.” Within those walls the sound of CAN took shape. As David Stubbs points out in his Future Days book, “The isolation of Schloss Nörvenich and the lack of any outside influence in terms of commercial and artistic direction, sound engineering or production meant that they had absolute freedom to become whatever they saw fit to become, with no preset plan or pre-written material.”

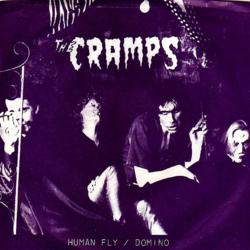

The Cramps

‘Human Fly’

Dusty brought us to Memphis at the beginning of this journey into musical journeys. Here we are, once again: from the American Sound Studio with its big stars of soul to the Ardent Studios of Big Star. This time around, it’s time for the Memphis of cult guitars to shine: we find some California-by-CBGB young rebels following their unlikely mentor, Alex Chilton. “I can take you to Memphis,” he just told The Cramps after seeing them live in New York. There’s no need to ask them twice: they’re all crammed in a drive away car in no time. Next stop, Tennessee. The Cramps release their Gravest Hits EP, produced by Chilton,in the Summer of 1979, just seven years after Big Star’s own debut. “It was the opposite of our New York experience,” guitarist Poison Ivy would later say. According to lead singer Lux Interior, “It was really great with him, because he was basically fucked up and getting loaded, falling asleep on the console. It was so different from our other experience, where a man behind the glass would command, ‘Go! Be creative now!”

The Rolling Stones

‘Happy’

Back to France. We started from mid 60s Paris, with the guidance of Marianne, and we’re coming full circle – fast forward to the early 70s, pleased to meet Marianne’s notorious cohorts. Sometimes the reasons behind artists’ mythic travels are not exactly as graceful and poetic as we love to imagine. You take a title like Exile on Main St. and you can’t help but imagine modern day Byrons…perhaps even a long-haired Trotskywith an electric guitar. As a matter of fact, in 1971 the Rolling Stones chose to live as arguably less romantic tax exiles. Hey, we’re not here to judge. What we can assuredly say is that Keith Richards had the laudable idea of renting a villa in Nellcôte, near Nice, and invite his bandmates over for some inspired recording sessions. One of them would be remarkably casual: an after lunch in the basement, and by tea time Keith had ‘Happy’, his signature single.